Money, money, Money… Who’s the common denominator?

Özgen Acar

What did Napoleon say? “Money… money... money...”

What did Napoleon say? “Money… money... money...” Who invented money to become the world’s richest person? Wasn’t it the Lydian King Croesus, who printed money containing electrum in Sardis, present-day Salihli, Manisa, in the seventh-century B.C.?

Lydian electrum coin

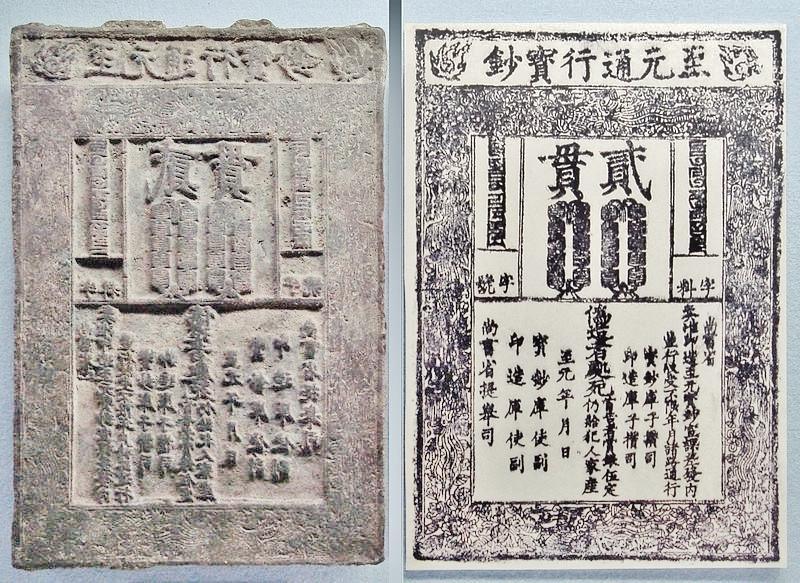

Who came forth in economic history with paper money, called banknotes? Wasn’t it the Mongolian Khan Kublai?

Throughout history, commemorative coins have been printed in various countries for celebrations. The first known commemorative coin was the Athens Deka (10) drachma, which was printed in 479 B.C. in ancient Greece to celebrate victory against the Persians.

Athens Deka Drachma

Some 1,900 silver coins, which were discovered in Antalya’s Elmalı district in 1984 along with 14 Athens Drachmas, were called the “trove of the century.”

I received two emails, one from London and one from Ankara, related to banknotes in one week. The one from London was about the newly opened Banknote Gallery in the Bank of England, which is the Central Bank of the Brits.

The director of the museum, Jennifer Adam, explained that newly printed money with polymer-e (a chemical compound) was also on display.

“The first banknote was used by Chinese people in 140 B.C. at the time of the Wu-ti Dynasty; it was gradually taken out of circulation until the Mongols. The Mongol khan had paper money printed for the first time between 1260 and 1290.

Kublai banknote and printing tool

The Uighurs used the money, called ‘Kumdu’ – seals printed on pieces of fabric – in the 11th century. Also in the northern Black Sea … the Suvar Turks put Ekin [fabric money] instead of paper, in the economy. The Bulgarians of Idil and the Khazars used leather money,” she said.

The mail from London continued: “Europe’s first paper money was printed in 1666 by the Stockholm Bank in Sweden. In 1672, paper money, called Goldsmith, was released to the market in England. In 1690 in America, the British Massachusetts colony released the first paper money in return for soldiers’ salaries. It was followed by other colonies. The formation of paper money in France started with the private bank La Banque Générale, founded in 1716.”

The first Ottoman silver coin, akçe, is believed to have been printed in 1326 in the Orhan Gazi period but a coin printed by his father, Osman Bey, the founder of the Ottoman Empire, was recently found.

Osman Gazi coin

Mehmed the Conqueror established the world’s first big mint in Istanbul’s Simkeşhane area. According to Ottoman documents, the most common implementation in the economy was the barter of property and service.

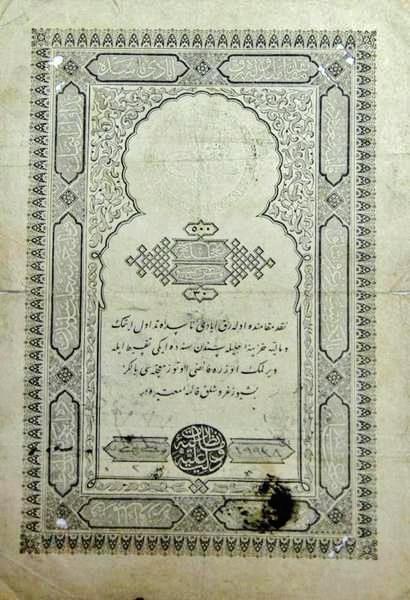

The mail from Ankara was about the first Ottoman money bill. This was the statement from collector Necati Doğan, who has written various books on the issue: “The sixth emission paper 500 kuruş, which was put in circulation by the Ottoman sultan Abdülmecid in 1851 but [which did not survive until] today, has been discovered in Ankara. The pattern of this money is at the Turkish State Mint.

The Ottoman money at the Turkish State Mint.

On the front of the banknote is Abdülmecid’s flowery embossed signature, the words ‘500 kuruş’ and the statement that it has 6 percent interest. On the back of the banknote is the seal of the finance minister at the time, Abdurrahman Nafiz. Its lithographic printing in size of 134x197 millimeters is thinner than current banknotes.”

Last year in a statement, Doğan said: “I found the fifth emission paper 500 kuruş, which was printed by the Sultan Abdülmecid in 1849 and did not survive until today.” Doğan says that both banknotes are unique right now.

At the time of the Sultan Mahmud II, the economy was shattered by riots and wars. Great Britain, which helped the Ottomans during the Egyptian revolt, was provided important economic privileges. Taxes were removed from trade, and customs duties decreased from 13 to 3 percent in 1841.

When similar agreements were made with other European countries, the import cost increased, troubles appeared in international payments and the value of Ottoman money fell. Customs duties were removed for foreign traders but because it was still in force for local traders, the Ottomans no longer controlled trade and the state failed to pay the wages of civil servants.

Sultan Abdülmecid, who declared the Imperial edict of Gülhane, printed the first banknote, “Kaime-i Mu’tebere-i Nakdiyye-i Osmâniyye,” in the Ottoman Empire in 1840.

The first Ottoman banknote

An amount of 20,000 liras, which was necessary to put banknotes on the market, was borrowed from the sultan. The term of the loan was one year at 2-2.5 percent interest. The first banknote was not printed but written in hand. This banknote of 16 million kuruş (32,000 pouches) was legal tender both inside and outside the country. In the event of the death of its possessor, it was passed down to his successors.

When the denominations were deemed insufficient, new banknotes of 24 million kuruş (48,000 pouches) were put on the market in the same year. These banknotes were set to remain in circulation for eight years at an interest rate of 12.5 percent.

The banknotes created two problems. First, people did not use these banknotes that were supposed to be in circulation in order to get their interest, therefore, the problem of cash money appeared in the market. Second, forgers easily put fake banknotes on the market because it was not printed but written by hand.

When these problems shattered people’s trust in banknotes, a decision was made to withdraw them from the market and print metal coins. Banknotes of 2.5 million kuruş (5,000 pouches) were destroyed and replaced with new version of banknotes.

An interesting method was applied in 1878 to prevent the problem of cash in coins. Cardboard was attached to the back of postage stamps to create coins.

The currency was akçe, the silver money. At first, the akçe was in fixed weight but it has frequently changed because of economic disruptions. Copper was included in silver in around 1898. The money made with this mixture was called “metelik,” a corruption of the word “metallic.” The word “metelik” has not survived until today, but the idiom “metelik bile etmez” (not even worth a penny) has.

Meanwhile, kuruş, which took its name from the Persian King Cyrus, who defeated the Lydian king Croesus, was put on the market. In accordance with the Kavaim-i Nakdîye Nizamnamesi, Sultan Abdülhamit II made a law to arrange the financial economy. The Turkish word “para” (money) comes from the Persian “pare” (piece).

During World War I, Brits engaged in forgery in an attempt to destroy the Ottoman economy, printing fake, 10-lira banknotes during the period of Sultan Vahdettin.

Fake banknotes

At first sight, it was hard to differentiate this banknote, which was printed by the British War Council in 1918, from its original. But the paper of the fake money was thicker and the small writing on the back were printed in reverse.

A vessel named Yorkshire, which brought the money, was sunk by German warplanes in the port of Piraeus in Greece, and the fake banknotes floating in the water were looted.

Even though some money seized by the Greek government was destroyed in Turkey, neighboring traders fooled people who were not aware of the event. The Turkish Republic worked hard to collect the money from the market, even as late as 1945.

The last Ottoman currency was valid in the Turkish Republic until 1928.

Just like the Banknote Galley is important in England, the Ottoman Bank Museum in Istanbul is important in terms of Ottoman money. One of the museum officials, local Istanbul historian Lorans Tanatar Baruh, explains the most interesting banknote, saying: “This banknote may be an answer to the Ottoman movements at that time. This is why it was printed in French, Ottoman, Arabic, Armenian and Greek. Even though it was in circulation for a short period of time, it is the most interesting piece in the museum collection.”

Ottoman money in various languages

There are other museums related to Ottoman and Turkish money at the Darphane (Mint) Museum in Topkapı, which features nearly 2,571 examples of money, medals and orders dating from between 7 B.C. to 1921. A ruined Ottoman mint was also restored and turned into a museum by Bursa Metropolitan Municipality. The museum displays the first coin printed by Orhan Gazi as well as currencies printed in Bursa mints.

The Turkish Republic printed its first metal coins in 1924. The first coins in circulation were in four types, 100 “money,” 2.5 kuruş, 5 kuruş and 10 kuruş. The smallest metal currency unit, 10 “money,” was printed in 1940.

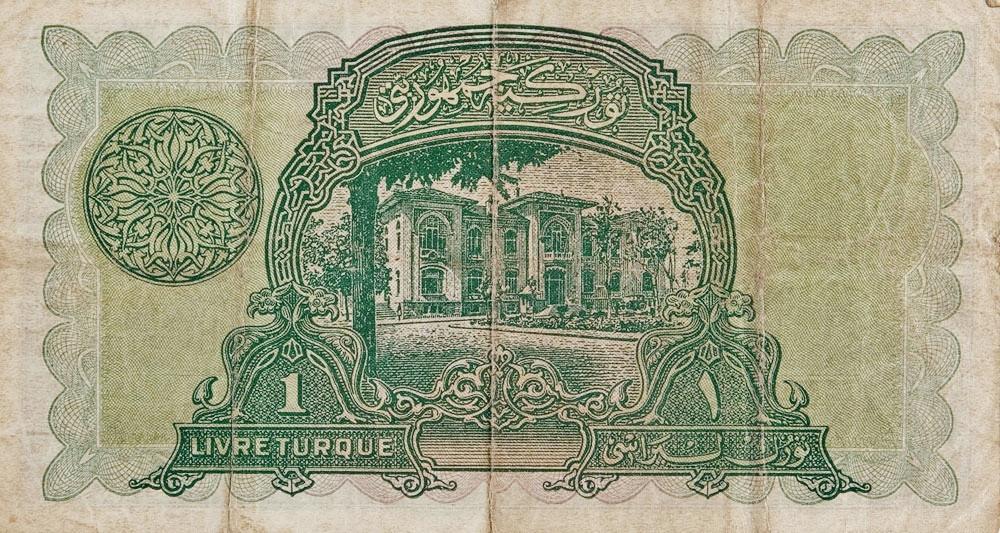

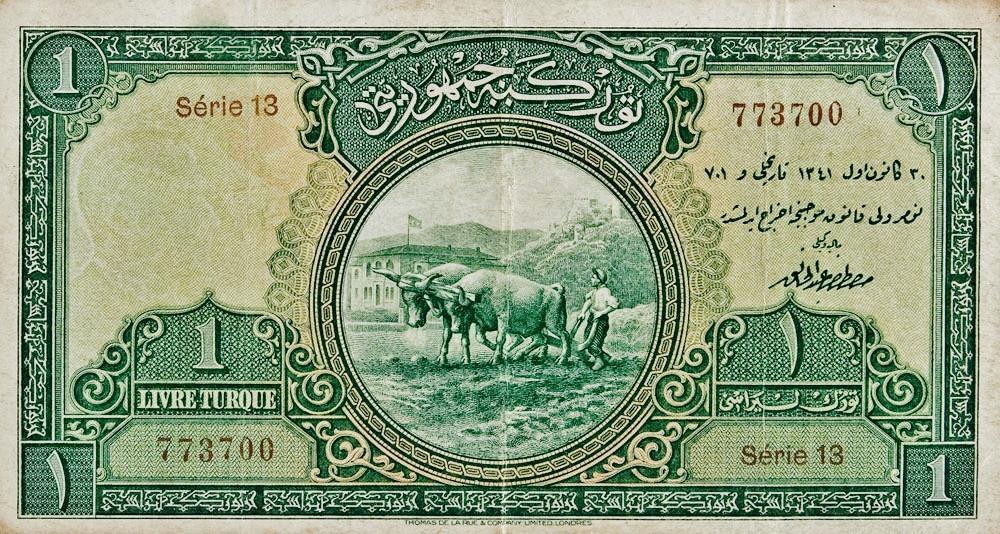

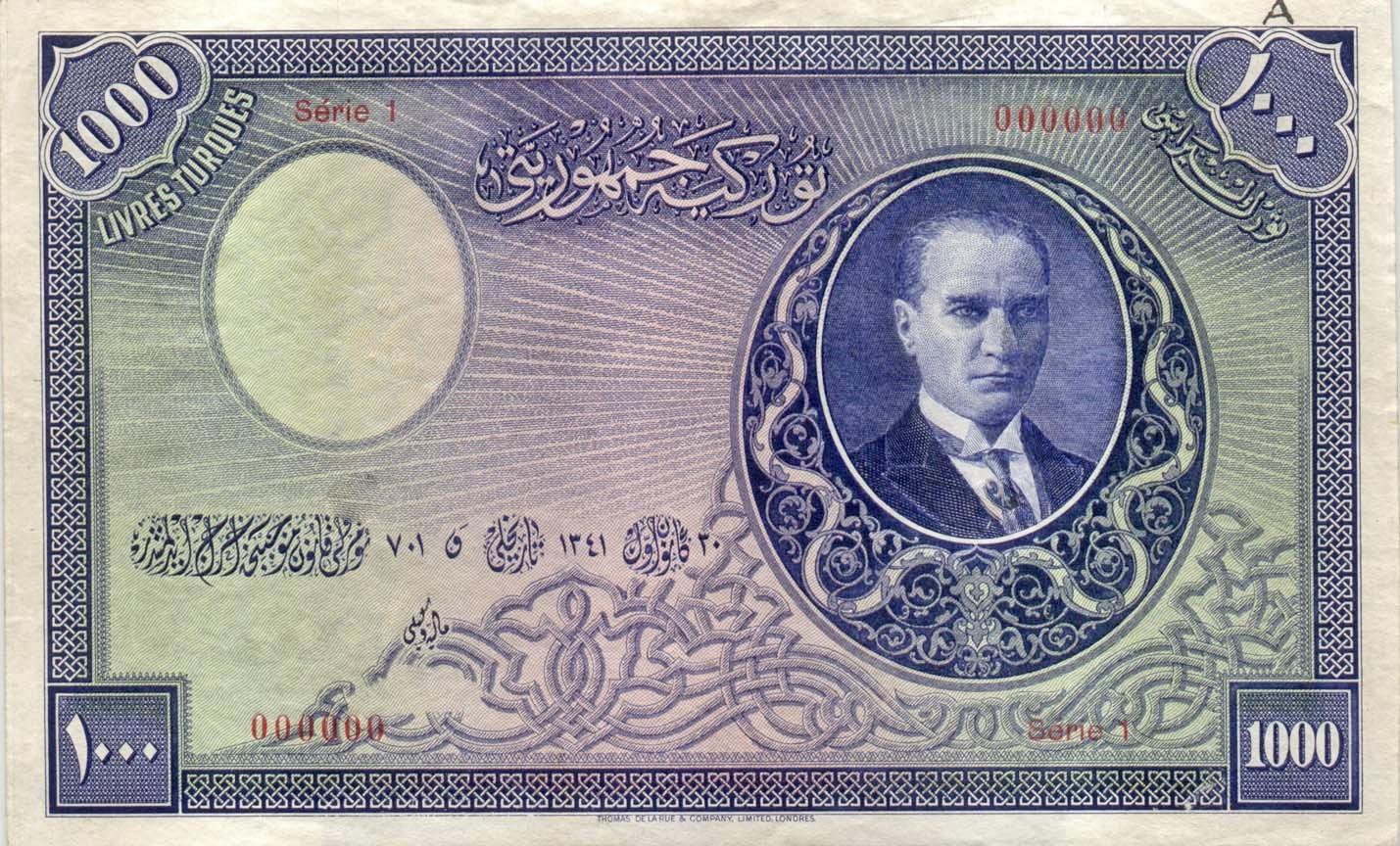

The first banknote in the republican era was printed by the British Thomas de la Rue company in 1927 in return for 88,000 English golden bars.

The front and back sides of the first money of the Turkish Republic.

Since the alphabet reform had not started yet, it was printed with the former alphabet in French. It was signed by Finance Minister Abdülhalik Renda.

The front side and back sides of the most valuable Atatürk money.

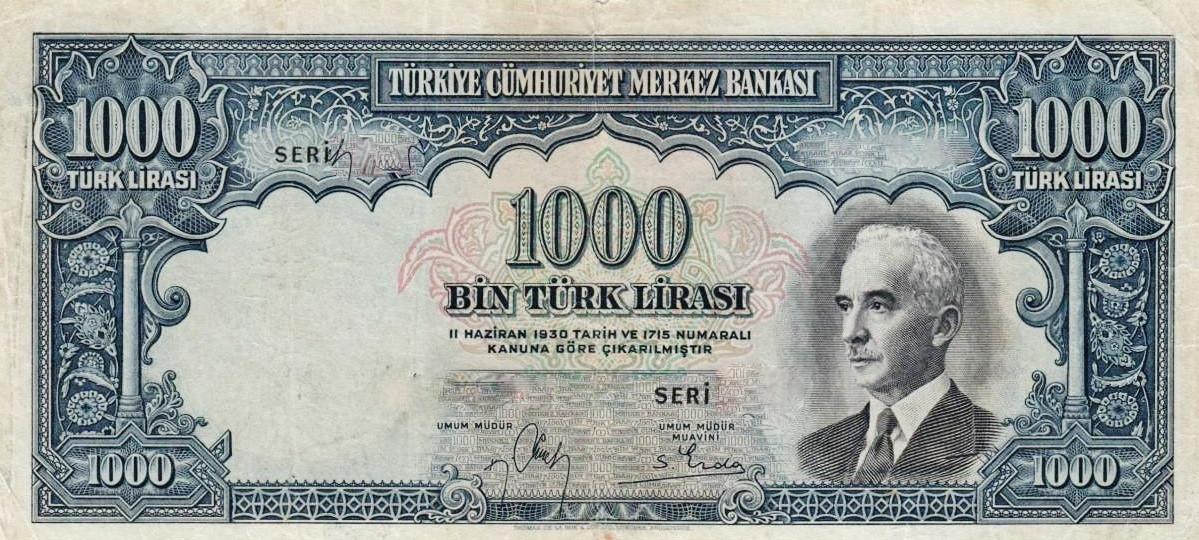

Later on, in accordance with the tradition of “presidential photos” in ancient and contemporary world currencies, presidents Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and then İsmet İnönü’s portraits were printed.

The portrait of İsmet İnönü on a bill

After 1950, only Atatürk’s photo was printed. Liras with the Latin alphabet went into circulation in 1937.

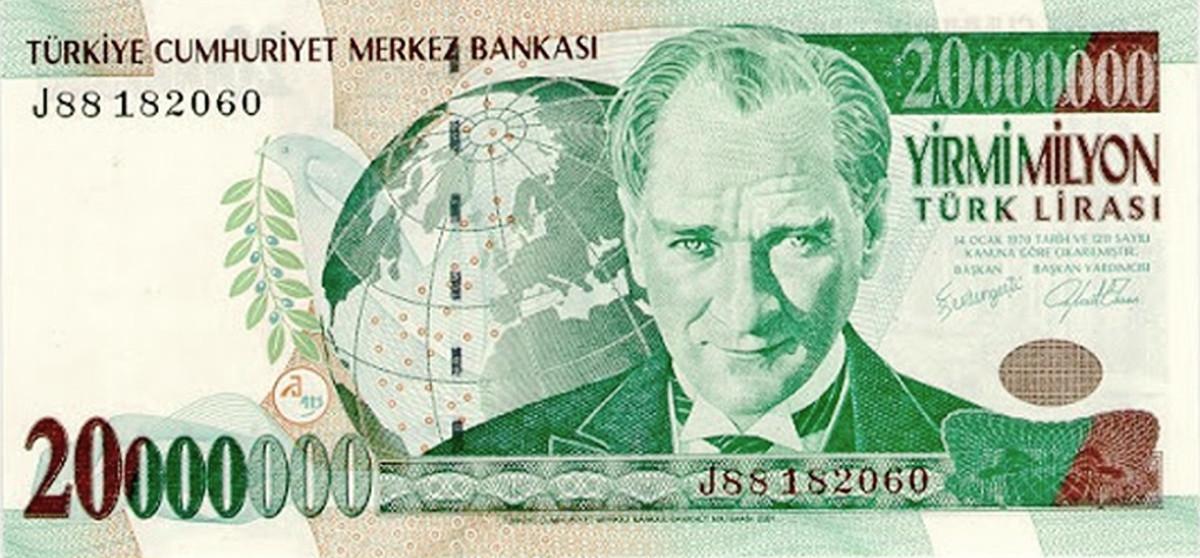

As a result of the great inflation in the 1990s, banknotes of 250,000 liras and then even 20 million liras were put onto the market.

Six zeros were emoved from the money

When inflation was brought under control, six zeros were removed and the name of the money became the “New Turkish Lira” at the beginning of 2005.