Let's call Turkey's new İzmit bridge the 'Evliya Çelebi Bridge'

CAROLINE FINKEL

Today, March 25, is the anniversary of the birth of Evliya Çelebi, one of the greatest Ottoman men of letters. He is also one of the least-appreciated. As someone who has lived in Istanbul for many years, immersing myself of late in Evliya’s life and work, I remain perplexed that he is scarcely celebrated in Turkey today. His birthday presents an opportunity to remember this remarkable individual and to propose a way to right this wrong.

Today, March 25, is the anniversary of the birth of Evliya Çelebi, one of the greatest Ottoman men of letters. He is also one of the least-appreciated. As someone who has lived in Istanbul for many years, immersing myself of late in Evliya’s life and work, I remain perplexed that he is scarcely celebrated in Turkey today. His birthday presents an opportunity to remember this remarkable individual and to propose a way to right this wrong.Evliya was a courtier, a dervish, a historian, a geographer, a musician, a linguist, and much else. He was a wit and raconteur, and a man of boundless curiosity and energy, who travelled the empire and beyond, and wrote about his adventures in the 10-volume “Seyahatname,” or “Book of Travels.” The work is probably the longest travel account in world literature.

Evliya tells us in the “Seyahatname” that he was born on the 10th day of the month of Muharrem in the year 1020 of the Islamic calendar. 10 Muharrem is a particularly holy day for Muslims, and anyone with an eye to posterity would choose it as the time to come into the world. In the year 1020, 10 Muharrem equated to March 25, 1611, in the solar, Gregorian calendar.

Five years ago, the 400th anniversary of Evliya Çelebi’s birth was widely recognized, including by UNESCO, which named him one of their “men of the year.” Exhibitions were organized and conferences held around the globe. Yet in the short time since, interest in Evliya’s work has sunk to a nadir. Hopes expressed in 2011 for the establishment of academic institutes dedicated to him, and pleas for funding for big projects for the study of the many aspects of his text, have gone unheeded. His name hardly features in the school curriculum.

There have been a few signs that the indifference of a nation is not total, as unsung officials have been inspired to make local acknowledgement of Evliya’s uniqueness and modern relevance. Here and there you may notice “Evliya Çelebi” streets, and a handful of schools, cultural centers and neighborhoods named for him.

What can be the reason for the failure to value Evliya Çelebi and his work? Evliya’s “Seyahatname” was first printed (in part) at the turn of the 20th century. This edition was censored by order of Abdulhamid II, and the result was a perversion of the manuscript text from which it derived. Evliya seems to have been considered “dangerous,” and still today his work is not infrequently criticized for being obscene and full of untruths. Yes, some passages of the “Seyahatname” may be more explicit or racy than the sensitive-minded can endure, and his count of the number of, say, mosques in any place, may on occasion be empirically incorrect, but his is a towering work of literature, not a tract tailored for the approbation of the delicate among modern readers.

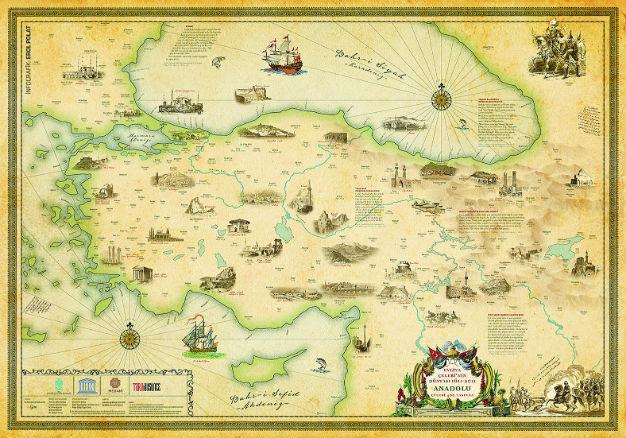

That the “Seyahatname” should be printed, and thus become widely available, was in large part due to the efforts of two men, Ahmed Midhat Efendi and Necip Asım (Yazıksız), who exchanged letters about this work in the newspaper İkdam. Contrary to the views of some intellectuals of their time, who denigrated the “Seyahatname,” they considered it a great achievement. Ahmed Midhat recommended that it be translated into European languages forthwith, that a map or maps showing Evliya’s travels be produced and that statues of Evliya be erected in every town and village as a source of pride for the people of the place.

Ahmet Midhat and Necip Asım’s dreams were dashed. In addition to the injustice of the “Seyahatname” being censored, few useful maps of Evliya’s travels have been drawn, and his work has still not been translated faithfully and in full into any foreign language. Statues of Evliya are few: I am aware of two in his family seat of Kütahya, a place that could surely capitalize on being Evliya’s native town, but where efforts to encourage public remembrance of the most notable of its sons have been underwhelming.

A century on, as we muse about Evliya Çelebi and his “Seyahatname” on the occasion of his birthday, it is not too late to make amends. A grand gesture is required – the modern equivalent of ubiquitous Evliya statues.

There is an obvious candidate for the honor of spreading Evliya Çelebi’s name far and wide. This is the new bridge being built over the İzmit Körfezi. It will be among the longest of its kind in the world, and across it will move thousands of people who will wonder who Evliya Çelebi is, and why they have not heard of him before.

Evliya himself travelled this way, crossing the Körfez en route to Syria in 1648 and again in 1671 on his pilgrimage to Mecca. On the northern shore he boarded a special boat constructed to carry his party with their horses, and disembarked after the short voyage on the quay of the peninsula (dil) at Hersek. His journeys are now marked in a very tangible way. The new bridge’s southern support stands foursquare in Hersek village, and the highway continues into Anatolia as Evliya himself once did. In 2009 we followed his 1671 itinerary, and we and others have since hiked, biked and ridden the route.

There can be no more fitting tribute to Evliya Çelebi and his “Seyahatname” than to dub the bridge across the İzmit Körfezi in his honor. There are many mega projects that require a name, but in this case “Evliya Çelebi Bridge” seems to be the only conceivable one.

*Dr. Caroline Finkel is author of “Osman’s Dream” (Rüya’dan İmparatorluğu’a Osmanlı); and co-author of “The Evliya Çelebi Way” (Evliya Çelebi Yolu), a guidebook to the early stages of Evliya’s pilgrimage route in western Anatolia. A generous selection of passages from Evliya Çelebi’s “Seyahatname” in English is “An Ottoman Traveller” (Robert Dankoff and Sooyong Kim).