Keeping warm, Ottoman style

NIKI GAMM ISTANBUL- Hürriyet Daily News

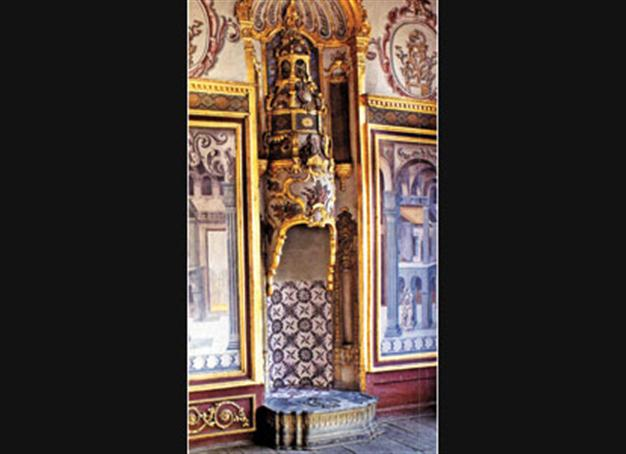

Braziers (R) could also be a work of art, made of copper or brass or even iron with designs such as the ones exhibited in museums. Another type of fireplace (photos above) found in the homes of the wealthy has an open hearth; the smoke would then exit from a chimney that would be covered with copper or more strikingly with beautiful tiles.

Charcoal was the fuel of choice for the Ottomans – heating, cooking and even making gunpowder. It was made by burning wood on hearths within the house and then transferred to various types of metal holders such as braziers that are salso exhibited in museums.“Winter has come early this year,” someone recently remarked. How comfortable we are with our natural gas heating or central heating units that consume fuel oil or coal. While that’s true for today’s big cities like Istanbul, it isn’t necessarily the case elsewhere and certainly not historically.

Did a real Prometheus bring fire down from Mt. Olympus or did some early ancestor of man accidentally figure out how to burn wood for warmth and cooking? However humans first arrived at a means of starting a fire on demand, they opened the way to migrate to cooler climes. Wood for centuries was no problem because the earth was heavily forested.

From burning wood to using charcoal was a small step. The Ottomans used charcoal not just for heat but for cooking and gunpowder as well. They used what was called black wood, particularly oak, and other non-fruit-bearing trees which were readily attainable from Anatolia. Willow was another tree that would be used for charcoal. Camel caravans and ships would bring already-prepared charcoal from as close as İznik or as far away as the southern coast of Anatolia. Wood, however, was also brought into Istanbul for processing.

For use in individual homes, wood would be burned twice a day – in the morning and again in the evening – to provide charcoal, if the latter was too expensive to buy ready-made for the household. The use of wood and charcoal for heat and cooking led to many of the fires that destroyed parts of the old city of Istanbul and although the sultans tried to insist that every house should have a way for its inhabitants to escape and keep water available for fighting fires, this didn’t stop hugely destructive blazes from breaking out all over the historic peninsula and in Galata.

Charcoal was made by burning wood on hearths within the house. The burning coals would then be transferred to various types of metal holders such as braziers. The brazier would be put under a table and the family would sit around it. A cloth would be put over the table and then over the laps of the sitters so they could keep their lower bodies warm at least. Coal was not discovered until the 1820s and even then it wasn’t considered a serious alternative to charcoal, at least not until the forests were seriously reduced in size and warships running on steam became an established feature in wars.

A brazier could also be a work of art, made of copper or brass or even iron with designs such as the ones exhibited in museums like the Topkapı Palace Museum. One whole unit of the Janissaries, the Tressed Halberdiers, was responsible for providing wood and charcoal to Topkapı Palace and especially for the Harem and the hamams there.

Another type of fireplace found at Topkapı and also in the homes of the wealthy has an open hearth; the smoke would then exit from a chimney that would be covered with copper or more strikingly with beautiful tiles. The chimney which might be two stories high would extend beyond the building with little caps covering them to keep the elements out. One has to assume that, although rooms were somewhat smaller than what we expect today, there were likely braziers set around as well.

Since most of the buildings in Topkapı Palace were paved in stone and marble, the cold was warded off with mats on top of which would be placed expensive carpets. Sitting areas were set on platforms. Windows had wooden panels or shutters that could be closed to keep out the cold. Curtains would be put along walls and over windows and even drawn around the sleeping platforms.

Clothing had to provide the rest of the warmth. Padding was used on undergarments, wool garments and felt were readily available. Because of sumptuary laws that regulated clothing, only high-level government officials and members of the Ottoman dynasty wore robes that were lined with fur. For the sultan to give a fur robe to one of his viziers or an official was a mark of high favor. Men were required to wear headgear of some sort, but only the official translators were allowed to don fur hats. Of course, they had to wear them during the summer as well so perhaps they lost some of their charm. The clothing depot at Topkapı has yielded many interesting items, including a pair of children’s boots that were lined with fur.

Istanbul would certainly have been cooler in Ottoman times than it is now, but people would surely have been used to it.