Journeys into the vanishing religions of the Middle East

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

'Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms: Journeys into the Disappearing Religions of the Middle East’ by Gerard Russell (Basic Books, 352 pages, $29)

'Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms: Journeys into the Disappearing Religions of the Middle East’ by Gerard Russell (Basic Books, 352 pages, $29)Twenty years ago, writer and historian William Dalrymple went on a journey among the imperiled Christian communities of the Middle East, chronicled in his classic book “From the Holy Mountain." Violent religious intolerance in the region has only accelerated in the years since, particularly after the catastrophic invasion of Iraq in 2003. The horrific advance of the so-called Islamic State and the dire consequences for tiny religious communities like the Yezidis has commanded Western headlines recently, but it is just the latest, grimmest expression of a process that has been ongoing for decades. As Dalrymple has written elsewhere: “The slow and still continuing unraveling of the vast multiethnic, multireligious diversity of the Ottoman empire has been the principle political fact of both the Middle East and the Balkans ever since the mid-19th century.”

This book, penned by former U.N. and British diplomat Gerard Russell, doesn’t just consider the imperiled eastern Christians, but also other endangered species of belief: The surviving pagan faiths that predated the coming of the three monotheisms - the Mandaeans and Yezidis of Iraq, the Zoroastrians of Iran, the Druze of Syria, Israel and Lebanon, and others. To illustrate his subject, Russell writes vividly in his introduction: “Imagine that worship of the goddess Aphrodite was still continuing on a remote Greek island, that worshippers of Wotan and Thor had only just given up building longboats on the coasts of Scandinavia, or that followers of the god Mithras were still exchanging ceremonial handshakes in subterranean Roman chapel. In the Middle East, in contrast to Europe, equally ancient religions survived.”

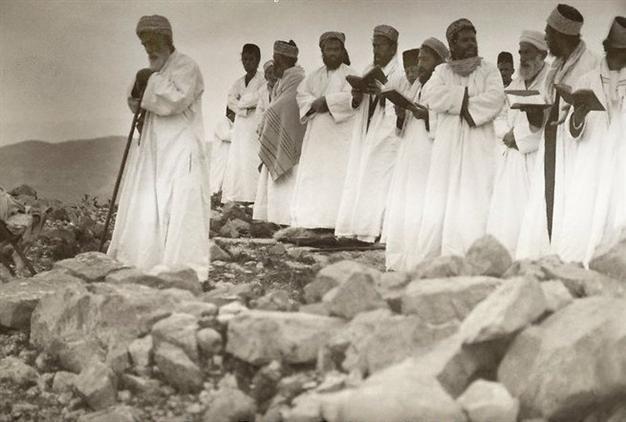

This book, penned by former U.N. and British diplomat Gerard Russell, doesn’t just consider the imperiled eastern Christians, but also other endangered species of belief: The surviving pagan faiths that predated the coming of the three monotheisms - the Mandaeans and Yezidis of Iraq, the Zoroastrians of Iran, the Druze of Syria, Israel and Lebanon, and others. To illustrate his subject, Russell writes vividly in his introduction: “Imagine that worship of the goddess Aphrodite was still continuing on a remote Greek island, that worshippers of Wotan and Thor had only just given up building longboats on the coasts of Scandinavia, or that followers of the god Mithras were still exchanging ceremonial handshakes in subterranean Roman chapel. In the Middle East, in contrast to Europe, equally ancient religions survived.”Russell travels around the Fertile Crescent speaking to various believers, attending their rituals, eating their food, exploring their history, and considering their invariably perilous present day situation. Though he’s entirely without arrogance or superiority, he almost has the air of a 19th century adventurer - intrepidly venturing into distant, exotic areas to mix with mysterious religious groups, the last vestiges of the magnificent civilizations of Persia, Babylon and Egypt in the time of the Pharaohs.

At times it can read like a catalogue of obscurity, and the balance between explaining and properly contextualizing these beliefs is sometimes slightly off. Obscurity fatigue is particularly acute in the first three chapters - on the Mandaeans, the Yazidis, and the Druze - most of whose adherents uphold archaic traditions but don’t even know the details of their own beliefs, and couldn’t explain them even if they wanted to (which they often don’t).

One of the book’s central themes is the tension between the ancient reality of these faiths and the modern political context. A particularly fascinating chapter sees the author visiting the Samaritans, “probably the smallest group of people to have retained over many centuries a national consciousness of their own,” who say their worship is the true religion of the ancient Israelites prior to the Babylonian Exile. Today’s Samaritans survive as a community of just 750 people in the Holy Land, and Russell stays with them in a small village on Mount Gerizim above Nablus in the West Bank. There, and in tiny pockets of Israel, the Samaritans guard a delicate neutrality, dependent on the goodwill of both the Israeli and the Palestinian authorities. In Russell’s words, the Samaritans are “the one issue the Palestinians and Israelis could agree about,” but for them - as for almost all other groups in the book - he can only see “a glimmer of hope.”

Joshua Landis of the University of Oxlahoma has suggested that the current upheavals in the Arab world are part of a wider “sorting out,” by which communities that have lived together peacefully for centuries in the Levant are finally being dragged apart, divided into their own separate “homelands.” It’s a process that Europe knows well, after experiencing the ripping apart of large multiethnic empires to be replaced by more cohesive, “ethnically pure” nation states in the 20th century. The process was traumatic, resulting in displacement, bloodshed, and the loss of many tangible and intangible things.

If something similar is indeed happening in the Arab world today, the tiny ancient faiths of the region may be one of the casualties. One of the most poignant passages in this book describes the visit of a group of Mandaeans to Russell. The high priest has lost all the male members of his family, and begs the author to make Britain accept as asylum seekers the few hundred left in Iraq. Russell is understandably taken aback and, reflecting later, rather depressed: “I had encountered the link to the ancient culture of Iraq that I had been looking for and it was vanishing before my eyes … with their departure, Babylon has truly fallen.”