Italian architect De Nari gets posthumous due with exhibit

ISTANBUL - Hürriyet Daily News

The rediscovered personal archives of De Nari, who came to Istanbul in 1895 and lived here for 60 years until his death, help confirm the real designer of many buildings.

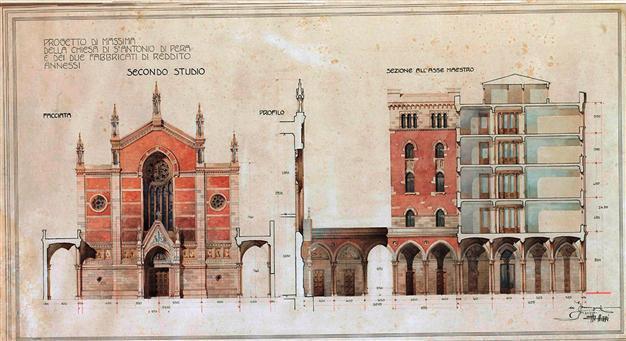

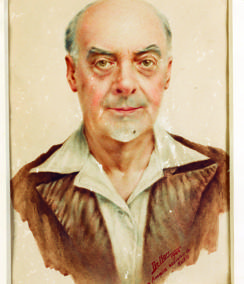

Having already featured the work of Raimondo D’Aronco and Henri Prost, the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Istanbul Research Institute is now turning its attention to Italy’s Edoardo de Nari as part of a continuing exhibition of architects that have left their mark on Istanbul.The exhibition, compiled from the private archives of Büke Uras, as well as different collections, not only stands testimony to the interesting life and career of the Italian architect’s life between 1895 and 1954 but also provides an architectural and social reading of the first half of the 20th century in Istanbul through a multifaceted individual.

Colorful period of transition

Although De Nari, who was active during the intriguing and colorful period of transition from the end of the Ottoman era to the first 25 years of the young Republic, may have been neglected in the history of local architecture, he nonetheless stood out in the architecture of his period in Istanbul. He was gifted in many areas and possessed qualifications that allowed him to practice his professional career in foreign lands, such as being an architect and engineer.

While revealing the real designer of a number of buildings whose architect remained unknown or ambiguous to date, the exhibition “Architect of Changing Times: Edoardo De Nari” also reflects, through the different styles of the architect, the aesthetic proclivities of a cosmopolitan upper class enjoying their final days in Istanbul. The memories, letters, journals, photographs, documents, and drawings comprising the exhibition not only provide us with a glimpse into the daily life and social circle of the architect but also mirror the sorrowful final period of a Beyoğlu bourgeoisie and a cosmopolitan Istanbul that no longer exist today, according to the show’s organizers.

De Nari is a forgotten player of this transition period that was equally heterogeneous, colorful and intriguing.

De Nari is a forgotten player of this transition period that was equally heterogeneous, colorful and intriguing. The rediscovered personal archives of De Nari, who came to Istanbul in 1895 and lived here for 60 years until his death, help confirm the real designer of many buildings whose architects were previously undetermined, uncertain or wrongly attributed to others.

De Nari’s architectural life began with the new century and transpired under the influence of the historic changes of the period. It can be argued that his architecture fully reflected this period of transition. Moving from historicism to eclecticism, to art déco in particular following the First National Architecture movement of the 1920s, it finally converged with the modernism of the 1940s and 1950s, according to experts on his work.

The early years of De Nari’s career is closely linked to his partner Giulio Mongeri’s professional activity. Lasting from the onset of the century until the 1920s, the partnership between the two architects that shared an office and co-designed a number of project is particularly important in terms of understanding the development period of his architectural career.

One of the defining factors of De Nari’s architecture was the importance given to detail. His buildings emerge as integrated designs comprised of complementary, interconnected, meticulously and individually executed singular units in which there is no clear distinction between different production channels such as architectural and industrial design. In this respect, craftsmanship and collaboration with craftsmen stand out as an equally important factor as art. The true architectural and social significance of De Nari lies in his role in visually representing the disappearing Ottoman bourgeoisie, the Pera circle, which constituted the upper class of its time, and the financiers of the early Republic era.

De Nari’s design process

De Nari’s design process cannot be defined by an absolute style. Lasting more than half a century, his long professional life shows variances in terms of typology and client profile, according to architecture experts. One of his earliest works is a residential building on Nane Street in Beyoğlu, as documented by some of the drawings encountered in his archives. While the related drawings do not bear his signature, they are quite possibly designed by De Nari, as they are included in his archives. Along with certain classical associations such as the lines of the building, the mansard roof, the triangular pediments above the windows, the cornices, and the use of bay windows, the building reflects a style paralleling eclecticism. Rather than an academic style, the strong influences of Levantine architecture and particularly of local masters are palpable. The building underwent considerable changes before reaching its current state, which makes it difficult to understand the original project.

An architect of changing times

De Nari was born on Feb. 16, 1874, in the city of Chiavari near Genoa. The master’s architectural life began with the new century and continued under the influence of the historic changes of the period. It can be argued that his architecture fully reflected this period of transition.

During the years in which De Nari worked in Istanbul and created his designs, the country was transformed through momentous and dramatic events such as the Italo-Ottoman War, World War I, the occupation of Istanbul, the birth of the new Turkish Republic, and the relocation of the capital from Istanbul and Ankara.

The graphic and linguistic changes observed throughout the rarely encountered integrity of De Nari’s personal archives across a wide and critical historic process allow us to pursue the transformation of his client profile from cosmopolitan individuals constituting the economic backbone of the empire to the Turkish clients of the early Republic. Furthermore, the gradual disintegration of a local minority tradition uprooted by immense social traumas can be witnessed through the drawings. In this regard, the De Nari archives extend far beyond an architectural collection and serve as a social mirror that reflects the massive transformations the city underwent.