Islamic saints in Ottoman Istanbul

Niki Gamm

‘Saints’ tombs are a characteristic feature of the landscape in most Muslim countries, where, whether associated with mosques or isolated, they are popular centers of visitation,’ according to Arthur Jeffery’s book ‘Islam: Muhammad and his Religion.’

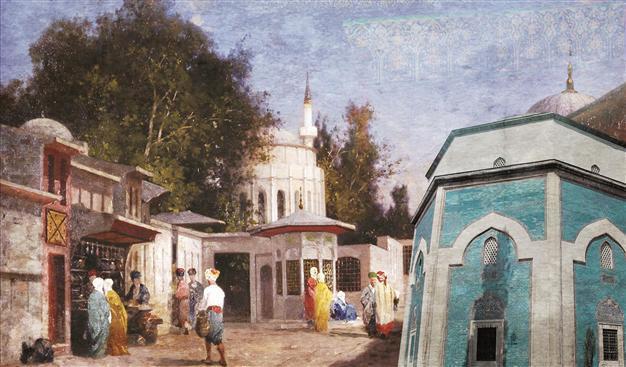

One of the traditions of Ramadan is to visit the graves of relatives; another tradition that isn’t just carried out at Ramadan is to visit the grave of a saint in spite of the fact that saints are not supposed to have a place in orthodox Islam. As Arthur Jeffery says in his book, “Islam: Muhammad and his Religion,” “Saints’ tombs are a characteristic feature of the landscape in most Muslim countries, where, whether associated with mosques or isolated, they are popular centers of visitation. The orthodox divines have spoken frequently and vigorously against this practice of visitation, but the consensus of the community has almost everywhere proved stronger than the condemnation of the theologians and the common folk still visit the tombs of saints to pray, to leave ex-votos, to seek blessing [Baraka] and the intercession of the holy persons buried there.”This held true for the Ottoman Turks and today we have many reminders in Istanbul of this tendency to look on certain people as saints, as men and women who had, before and after death, characteristics that would benefit those who prayed for their intervention. They were addressed as veli (saint), pir (spiritual guide), aziz (saint, holy) or baba (father) and they might have achieved this status while still alive or afterward in the grave. What made the person a saint might be his ability to perform miracles, answer prayers, provide advice or assistance and the like.

Mysticism or the seeking of union with the divine truth (God) arose in the years following the death of the Prophet Muhammad in the seventh century AD, not surprisingly so since the early Muslims lived in a geographical area in which, for example, orthodox Christians worshipped people they considered saints.

Islam also has an abstract quality about it in spite of its rules for everyday life and as such was not as appealing to the uneducated, who preferred something they could touch and turn to in a physical sense.

Often referred to as Sufism after the wool (suf in Arabic) clothing worn by its early practitioners, the mystic movement spread rapidly and divided into separate groups under different leaders who were often regarded as saints. The further away from the central heartlands of Islam, the more likely it was that converts would continue with their old customs, albeit with some adaptive strategies. These “saints” were known for their discipline, leadership, self-denial and they were surrounded by disciples who wanted to learn their “road” to achieving perfection and unity with the divine being.

As the eminent Islamic scholar Fazlur Rahman has explained in his book, “Islam,” “But the directly religious motivation was not the only factor in the spread of the Sufi movement. Its socio-political function, and at times more specifically its protest function, were even more powerful than the religious one. Sufism offered, through its organized rituals and seances, a pattern of social life which satisfied the social needs of especially the uneducated classes. This, more than anything else, explains the widespread success of the ‘rustic orders’ of the villages removed from the cultivated influence of the city life. This was particularly the case with those orders which freely indulged in practices of singing, dancing and other orgiastic rituals.”

Rahman added, “Besides Sufism’s ‘appeal to the heart’ at the higher spiritual level, it unfolded a disconcerting tendency of compromise with the popular beliefs and practices of the half-converted and even nominally converted masses. Within its latitudinarianism, latent in it from the beginning, it allowed a motley of religious attitudes inherited by the new converts from their previous backgrounds from animism in Africa to pantheism in India. A typically Sufi Hadith [tradition], according to which the Prophet said, ‘God the Exalted says, “I am what My servant thinks of Me,”’ was given wide currency and curious interpretations by eminent Sufis.”

As time went by, some of people who joined these sects did so for less than religiously reasons and more because of the possibility that the association with their members might bring advantages. One such was the Halvati sect under the Ottomans that for a time had a close relationship with the imperial family, that is, Bayezid II. The latter credited the leader of the sect at that time with helping him gain the throne on the death of his father, Fatih Sultan Mehmed and even presented him with a former Byzantine church that was converted into a lodge.

Another sect was that of the Bektaşis, whose members were most often connected with the Janissary military corps. The Mevlevis for their part had many members in high positions throughout the state bureaucracy. The Halvatis continued throughout the Ottoman centuries but on a lesser scale under leaders who were not involved in politics while the Bektaşis were driven underground or into the Balkans following the abolition of the Janissaries in 1836.

Ayhan Yalçın in his book “Istanbul Evliyalari ve Ziyaret Yerleri” (Istanbul Saints and Visiting Places) lists 740 individuals’ grave sites that range from the imperial mausoleum of Fatih Sultan Mehmed and the tomb of Eyüp Sultan to the humble grave of Haydar Baba in Üsküdar amid the train tracks behind Haydarpaşa Train Station with its sign asking that candles not be lit there. If you live in an older part of Istanbul, there’s undoubtedly one nearby.

A book by municipality

Some saints’ tombs are described in the latest publication of Istanbul Greater Municipality’s Culture Inc., “Istanbul’un 100 Türbesi,” which includes photographs, although the book concentrates mostly on the mausoleums of sultans and famous people. In Istanbul there are 120 official türbes, according to the Directorate within the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The Greater Istanbul Municipality oversees their upkeep and restoration.

About 10 percent of these belong to Ottoman sultans with a certain number of people who were members of the imperial dynasty including women. Of the others, they were either high court officials or the leaders of sufi sects. The tombs of local saints are usually maintained by people who live in the area and are apt to offer up prayer whenever they pass by. Often they’re in the small cemeteries that were established alongside the lodges in which the saints lived and practiced their beliefs. Sometimes the worshipper will leave a small, written petition or light a candle. Occasionally he, or more likely she will ask for a charm or amulet to take home in the hope that it will prove efficacious.

Praying to saints and at saints’ tombs may be rejected by orthodox Islam, but it has never been possible to stamp the practice out completely.