Humor magazines continue to power Turkish pop culture

Emrah Güler

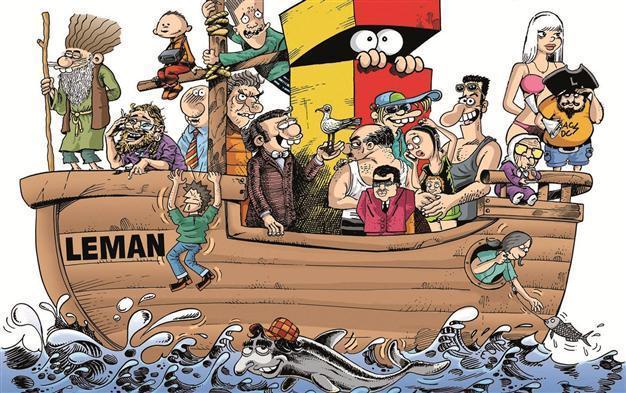

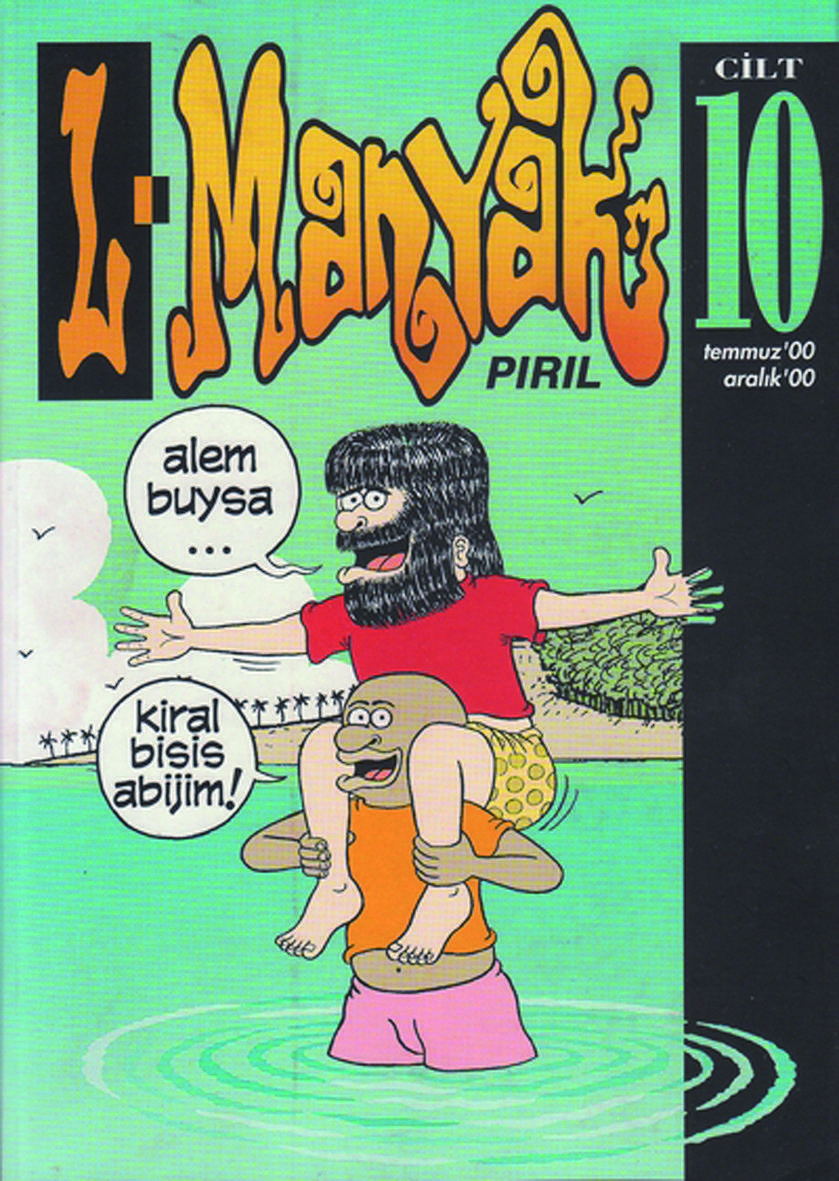

'Leman' and its offspring 'L-Manyak' helped launch some of the most subversive, crude - but undoubtedly inspirational and entertaining - characters and comics in Turkish history.

As we celebrate the anniversary of the publication of the very first Ottoman humor magazine, little seems to have changed. The experiences of “Diyojen” (Diogene), first published in 1870, heralded a tradition of the state being none too happy with political satire and antagonism under the guise of humor, opting for censorship.

As we celebrate the anniversary of the publication of the very first Ottoman humor magazine, little seems to have changed. The experiences of “Diyojen” (Diogene), first published in 1870, heralded a tradition of the state being none too happy with political satire and antagonism under the guise of humor, opting for censorship.The publisher and founder of “Diyojen” was Teodor Kasap, a Greek Ottoman, who was also the first cartoonist to be imprisoned for his work in this country. The infamous cartoon that led him to prison featured the traditional shadow puppets Karagöz and Hacivat, in which one of them is handcuffed and the other talks about freedom (or lack thereof).

Sultan Abdülhamit II (r. 1876-1909) later prohibited the publication of humor magazines within the Ottoman Empire, forcing them to be printed in Europe and the Middle East. This prohibition included “Diyojen” and later its successors “Hayal” (“Imagination,” or “Dream”), “Tokmak,” “Caylak,” and many others. Censorship transformed into auto-censorship with the publication of the longest-running humor magazine “Akbaba” (Vulture) in 1922.

“Akbaba,” whose first issues coincided with the first years of the newly-founded Turkish Republic, continued a tradition of staying in line with the ruling parties, shutting off any opposing voices among its writers and cartoonists. Although it featured the works of critical voices such as Cemal Nadir, Turhan Selçuk, Semih Balcıoğlu, and Aziz Nesin throughout its course until 1977, it never veered away from its close stance with the government.

Until the 1970s, there was really only one humor magazine that had featured satirical commentary on politics and served as an opposing voice. The weekly magazine “Markopaşa,” run by some of the greatest intellectuals of the time such as Sabahattin Ali, Aziz Nesin, Mustafa (Mim) Uykusuz and Rıfat Ilgaz, was banned, censored, and had to change names seven times over the course of its short lifetime between 1946 and 1949.

Crude but inspirational characters

Crude but inspirational charactersThe humor magazine that particularly made history in Turkey, which changed the face of humor and transformed it from an intellectual endeavor to pure pop culture was “Gırgır.” The magazine was first published in 1972 by Oğuz Aral, a legendary cartoonist who became a teacher and inspiration for generations of cartoonists to follow. At one point, it had a circulation of half a million copies every week, and became the third best-selling humor magazine in the world.

“Gırgır” was a blend of political satire, never refraining from criticizing leading politicians, and erotic humor aimed at urban youths. Later, the erotic content, exemplified by photos of naked women and comics like “Utanmaz Adam” (The Shameless Man), transferred to the magazine’s offspring “Fırt,” while political satire and opposition dominated the style of “Gırgır.”

“Gırgır” also took humor magazines from the clutches of intellectuals and turned them into something accessible for the masses. This, in turn, attracted criticism for being banal and far from artistic. However, the style and spirit of the magazine stuck, opening the way for humor magazines of the recent past and today, which have not shied away from sexuality, slang, and curses.

Many humor magazines that came after “Gırgır” followed its size, dominant yellow coloring, and the featuring of political cartoons on its front cover and third pages. “Limon,” “Leman,” “Lombak,” “Uykusuz,” “Penguen,” and many others in recent decades have positioned themselves as opposing voices against the system, while continuing to include sexual material, entertaining the mishaps of sexually-frustrated Turkish men of every place and time.

“Leman” and its offspring “L-Manyak” stand out among the others, as they have both helped launch some of the most subversive and crude - but undoubtedly inspirational and entertaining - characters and comics in Turkish history. Cengiz Üstün’s “Kunteper Canavarı” (Kunteper Monster), the human-looking alien with a giant penis, is one of those, while Kaan Ertem’s “Zıçan Adam,” a bringer of justice who punishes those who disrupt social harmony by excreting on them, is another.

Perhaps the most famous of the characters that sprang from “L-Manyak” is Bülent Üstün’s “Kötü Kedi Şerafettin” (Şerafettin, the Evil Cat). A true thug of a cat, Şerafettin lives in Istanbul’s Cihangir area, bringing trouble to everyone in his vicinity. With Şerafettin now approaching two decades in print, a project to bring him to life in an animation feature film is about to take off. The project is a true testament to the enduring popularity of humor magazines in Turkey.