Human rights films becoming an integral part of cinema

Emrah Güler ANKARA - Hürriyet Daily News

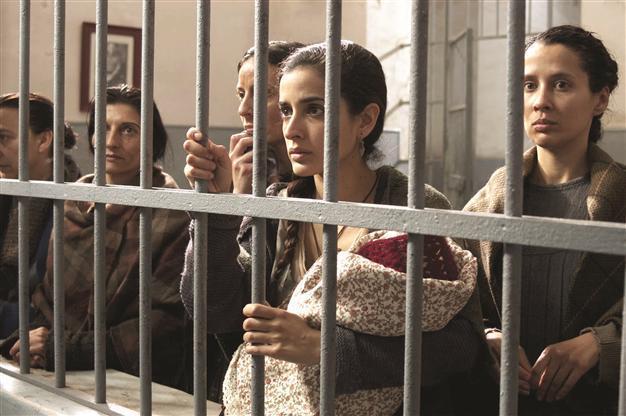

The Sleeping Voice

Moving images might be the single most powerful tool for propaganda, and it has been that way since the appropriation of cinema as a form of mass entertainment in the last century. Early Soviet cinema, the German and British cinemas of World War II, and, well, Hollywood cinema are just some that have used film for the blatant promotion of ideologies and political propaganda.If cinema has served as a powerful tool to impress masses by disseminating messages to promote dominant ideologies, it has worked the other way as well. The violation of human rights, wars, repression, oppression and censorship have also found their way into movie theaters, not from the point of view of those responsible, but from the oppressed.

Not until very long ago, films addressing human rights issues reached only small numbers of people, mostly those who were already aware of the issues. That all seems to be changing now. Film has become a widespread medium to inform, inspire and influence audiences around the globe on struggles small and grand, ongoing and historical.

Human rights film festivals are blossoming around the world, in places as diverse as Addis Ababa, Papua New Guinea, Nuremberg and Montreal. Features, documentaries and shorts are screened at these festivals, which provide a chance for people to network while also proudly advocating struggle and inspiring and informing people to challenge violations of human rights.

Films on human rights compete in Istanbul

There are human rights films networks, sections in film festivals devoted to human rights and awards dedicated to films focusing on human rights issues. The upcoming Istanbul International Film Festival provides a good example of the prominent international festivals’ approach to human rights.

For the sixth time this year, the Istanbul International Film Festival is featuring the Human Rights in Cinema Competition, with the Council of Europe Film Award going to one of the 10 films that hope to raise public awareness in human rights issues while promoting a better understanding of their significance.

The award requires competing films to address human rights, tolerance and social inclusion in line with the values and principles of the Council of Europe, namely the protection of individual freedom, political liberty and the rule of law. This year’s films also show the broad categorization that cover films on human rights. There are examples dealing with the recent histories of such countries as Turkey, Iran, Hungary and France. Some go to 1940s Spain, while others take a look at Eastern Europe during World War II.

As a rule of thumb, films on human rights violations are made by those who have some sort of affinity with the issue in question. The filmmakers are either from that specific region, or have already been part of some sort of activism on the issue to raise awareness. That’s why most of these films shine light on recent history or take place in the present day as they deal with the repercussions of struggle and oppression.

From World War II to today’s Turkey

Almost all of the films in the Istanbul International Film Festival’s Human Rights in Cinema Competition fall into that category. You can watch films from Iran, France, Turkey, Romania, Hungary and Italy as they take a look at the violations of human rights in their countries.

There are two films from Turkey in the section – “Simurgh,” journalist and director Ruhi Karacadağ’s take on the death fasts to protest the F-type prisons and the subsequent Return to Life operation, and Özcan Alper’s award-winning “Gelecek Uzun Sürer” (Future Lasts Forever), which takes a look at the “unnamed war” in southeast Turkey through the eyes of a young woman traveling to the region from Istanbul.

Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof’s “Bé Omid É Didar” (Goodbye) is inspired by his own imprisonment for crimes against the government. The film follows a young lawyer and the desperate measures she is willing to take to flee the country. The harrowing “Présumé Coupable” (Guilty) from France is the real-life account of Alain Marécaux and his wife as they are convicted for crimes they haven’t committed. Director Vincent Garenq questions the justice system in modern Europe.

Based on true events, writer and director Bence Fliegau’s “Csak A Szél” (Just the Wind) takes a look at the atrocities the Romany people have suffered in Hungary. The only animated feature of the section is from Romania. “Crulic – Drumul Spre Dincolo” (Crulic – The Path to Beyond) tells the true-life story of Claudiu Crulic, a Romanian who died in 2008 in a Polish prison while on hunger strike.

A few in the section travel in history to the early 20th century. Polish director Wojciech Smarzowski’s “Rózá” goes to the aftermath of World War II where the lead character finds hope in a life with a German officer after being forced into prostitution by the Soviets. “La Voz Dormida” (Sleeping Voice), by Benito Zambrano, takes the audience to a women’s prison in 1940s Madrid during Gen. Francisco Franco’s regime.

Some of the most powerful examples of cinema on human rights in recent history will be part of the Istanbul International Film Festival, and at least one will go home with an award.