‘Grassroots networks critical to success of Turkish Islamists’

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr ISTANBUL

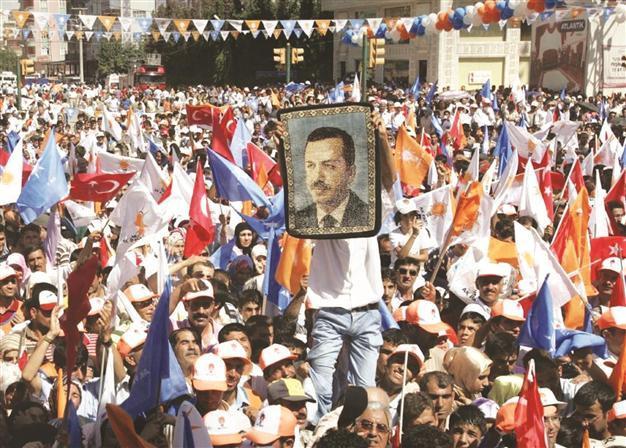

DHA photo

As Turkey heads for another general election this June, the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) is oiling up its formidable grassroots campaigning machine, which has steamrollered opposition efforts for over a decade.Political scientist Kayhan Delibaş’s new book, “The Rise of Political Islam in Turkey: Urban Poverty, Grassroots Activism and Islamic Fundamentalism” (reviewed here), explores the vital role that on-the-ground operations played in the advance of Islamism, drawing on the author’s extensive research with activists in Ankara at the end of the 1990s. Ideology was important, Delibaş argues, but it was the chaotic urbanization, economic strife, and the lack of organic links between voters and mainstream parties through the 1980s and 90s that really allowed the Islamists to flourish. The AKP’s forerunners won their initial successes in local elections thanks to their effective grassroots work on the urban periphery, which gave them a launch pad to national prominence.

The Hürriyet Daily News spoke to Delibaş about his book, the years of research that went into it, and what his findings tell us about Turkey’s political landscape today.

You argue that grassroots operations were in many ways more important than abstract ideology for the early success of political Islam in Turkey. Can you explain?

Throughout the late 1980s and 90s the main center-left and center-right parties were in a mess. For campaigning, these parties, exemplified by the Motherland Party of Turgut Özal, typically relied on the TV and broadcast media that was becoming widespread in Turkey at the time. They began to hire campaign managers from the U.S. and elsewhere to devise strategies to win votes. But of course this was limited. Throughout the period, especially during the 1990s, voters felt increasingly alienated from the main center-right and center-left parties, which weren’t really “mass” parties.

However, the Islamist party established in 1983, the Welfare Party (RP), grasped what was lacking. Its workers campaigned from door to door, from neighborhood to neighborhood. They also did many kinds of charity work, which helped them gain ground in poverty-stricken neighborhoods after the 1980s. The neoliberal policies of the 1980s created a massive flood of urbanization but there weren’t enough jobs in the cities to absorb those migrants, who ended up in a perilous economic situation. As a result, the RP was able to win the support of the urban poor through charity work and gaining their trust.

In the districts of Keçiören and Mamak in Ankara, where I did my fieldwork in the late 1990s and 2000s, the RP activists were very busy. I went to hundreds of neighborhoods, interviewing and meeting more than 2,000 people. The election in 1999 took place while I was conducting the research, which gave me a great chance to observe how activists operated on the ground at election time. I was able to see how effective they were at gaining people’s minds, as well as their hearts.

And the work they did wasn’t just during the elections, it was year-round.

Most of the people working in the neighborhoods told me, “Look, this is not just once every four or five years, we are not seasonal workers, we are constantly working and being in the neighborhood.” They were very active and dedicated, which gave them direct access to people. The RP’s women’s branches, which they called the “Ladies’ Committees,” were original and effective, and the party also had very active Youth Committees working in the neighborhoods. But of course most of the work was done by the male activists.

Can you give some examples of the work that the Islamist activists did to establish themselves in communities?

There are lots of examples. If someone had died, or if someone was ill, or if some other unlucky event happened, the party’s workers would go there to offer their condolences. Or if there was something like a wedding or a circumcision they would go to celebrate and perhaps take gifts. Another example was when people were ill. A few years ago, Turkey’s healthcare system was in a bit of a mess, and poor people often couldn’t pay for their hospital treatment. A more comprehensive insurance system was only later introduced. So the Islamist activists helped with that too, organizing mobile hospitals and dentists for those who couldn’t go to hospitals.

In those poorer neighborhoods, particularly the “gecekondu” (built overnight) shanty towns, services weren’t very well organized, so these activists would offer to help. They had connections with local artisans and shop owners, and get whatever they can from them - food rations, coal during the winter - which they then distributed to poorer people in the neighborhood.

Of course, being there with people in their neediest and most vulnerable times had a huge effect. The activists told me that they were not just there to win votes. In order to gain votes they first had to win their hearts and minds.

One of the activists you quote in the book says this kind of work used to be done by left-wing groups - he talks particularly about welcoming new migrants at bus stations and helping them settle in the city. To what extent did the Sept. 12, 1980 coup destroy the left’s ability to organize such activities? Did the coup’s repression of left-wing parties indirectly create the opportunity for Islamist activists to exploit?

The coup obviously had an enormous impact on Turkey’s political landscape. I think part of the genius of the RP and its leader Necmettin Erbakan was the way they borrowed leftist slogans and practices. All the old leftist groups had been concerned about the problems of the poor before the coup. They would set up committees and build entire “gecekondu” settlements, occupying land that belonged to the state and erecting hundreds of such neighborhoods across Istanbul. They would also set up cooperatives to provide cheap food for the poor. Of course, they were also quite vocal and active within the trade unions.

But the 1980 coup destroyed all the bases of the left. Up to 700,000 people were detained, thousands were arrested and convicted, and there were many executions. The coup was staged against leftist ideology and it crushed the entire left, which had been active and on the rise.

After 1980, for a long time, all leftist activity was harshly prosecuted. The Turkish-Islamic synthesis was made into the state ideology. The state hoped that this would be a panacea against the left and the communists on the one hand and the Kurdish separatists on the other hand. So having the implicit backing of state ideology allowed the Islamists to grow. They were almost given a free hand.

The Turkish political landscape was almost turned upside down after 1980. The right-wing conservative parties have generally been supported by the poorer sections of society, while the mainstream nominally center-left parties have been supported almost exclusively by the wealthier sections. It seems that this tendency really began after 1980.

In the 1990s, RP leader Necemettin Erbakan quite cleverly devised the idea of the “Just Order,” which became the party’s most important slogan. He aired the grievances and problems of the urban poor, getting their attention and attracting their votes. This is one of the ironies in Turkey: After the 1980s, the center-left abandoned its traditional bases, while the religiously-oriented or Islamist parties adopted the left’s slogans and policies, mobilizing the urban poor to support them. By the mid-1990s, the urban poor were in a bad situation and were looking for a party to air their grievances. Unfortunately, little was forthcoming from the social-democratic left.

The Islamist parties were also adopting rhetoric against neoliberal global policies, which made the parties of the left seem almost like bad replicas of the right-wing parties. So the division between right and left in the mainstream parties didn’t really exist any longer. The religious parties devised policies to air the views of poor urban voters and stepped into this vacuum.

Let’s project forward to the AKP. Islamist parties, particularly the RP of the 1990s, have employed anti-neoliberal rhetoric to appeal to poor voters. But its critics say with some justification that the AKP has built its success on neoliberalism. What was behind this huge shift?

There has indeed been a huge shift. There is a big contradiction between what they said originally and what they are now doing. The big test came with how Islamists would behave and what sort of economic policies they would carry out when they got into government. In the 1990s, the Islamist parties relied on the notion of the “Just Order,” talking about the economy and society, which was important for attracting poorer urban voters. But once the AKP came to power in 2002, it gradually aligned with free-market neoliberal policies. Now, after 12 years in power it has really become the main bastion of neoliberal policies in Turkey.

Probably the AKP’s biggest success has been managing to do both at the same time: Engaging with global neoliberal policies but convincing its support base that it is doing what it can for poorer neighborhoods. Billions of Turkish Liras have been spent on social work and social support, but the AKP’s critics are right that it has also been applying aggressive neoliberal policies. It has overseen some of the biggest privatizations of state-owned companies in Turkey’s history.

However, perhaps the biggest problem of the AKP’s model of social welfare is that it isn’t a modern, entitlement-based system, like in Germany or Britain. It is generally conducted through particular channels and directed to wherever the AKP is likely to get the most votes. It’s not a universal system, but more of a pick-and-choose system. In Ankara, for instance, the party knows which neighborhoods and districts are most likely to vote for it from the voter registries, and it keeps this in mind when delivering social welfare.

Politics is not only about what you are doing, but how you are showing it. If you are able to manage people’s attitudes and thinking successfully then you can do this. So as long as the government is able to find funds for its supporters, it won’t be undermined. It will continue to find support among those sections of society.

The AKP’s ability to control social security in power and its inheritance of the on-the-ground operation developed in the 1980s and 90s has created a very potent combination.

When they came to power, they knew how use these networks. After 2005, when Turkey officially became an EU membership candidate, the government had to modernize the country’s social security system. In line with those reforms it introduced new provisions - aid for disabled people, elderly people, unemployed people, etc. - so a quasi-universal social security system is now in place. But the bulk of state social assistance still comes in the same form that the Islamists were using in opposition. Of course, it is now on a bigger scale, with much greater funds and mechanisms.

Another contradiction is the idea of corruption and patronage. In the book you talk about how political Islamists in opposition complained about how mainstream parties were corrupt cartels relying on clientistic networks. But today the AKP is using the same means to reinforce itself in power.

This is ironic and also quite sad. The same allegations of corruption that destroyed all those old center-left and center-right parties in the 1980s and 90s are today being leveled at the AKP. All the old parties were accused for having clientistic approaches to politics, and the Islamists defined themselves against this. But now they are doing the same thing. In the end, what brought the Islamists to power could also destroy them. I wouldn’t say the situation is identical, but there is a resemblance.

However, in another sense it’s also natural for the poorest parts of the electorate to keep voting for the AKP. If you’re struggling to pay your bills, or your rent, then you aren’t going to be very selective about whether the help you receive is gathered improperly. You will simply vote for whoever is giving it to you. What’s more, the high level of polarization between the government and the opposition also allows the AKP to maintain its support. This polarization has helped support the patronage system that the government has developed.

But there’s a big difference between the effects of corruption and clientism today and its effects in the 1990s. Back then, support for the mainstream political parties fragmented in response to those things, while today popular support for the AKP remains strong.