Gift-giving on a grand scale at Ottoman Empire

NIKI GAMM Hürriyet Daily News

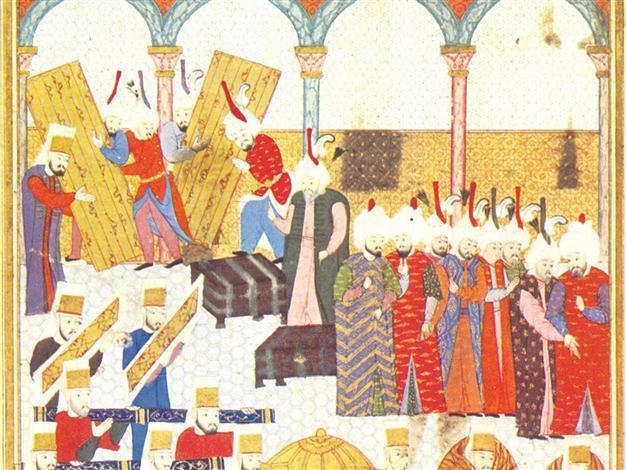

Gift-giving had an important role in diplomacy and had to be carried out with the greatest of care and consideration. Several gifts are still on display at Topkapı Palace.

As it is the holiday season, the story of the three magi or kings who came bearing gifts for Jesus at his birth comes to mind. The story was not told in the Qur’an, although it was known in Arabia at the time of the Prophet Mohammed. According to al-Bukhari, the story was translated by the uncle of Khadija, the Prophet’s first wife.But gift-giving has been a long-entrenched practice among all cultures, as far as we know, and the Ottomans certainly spent a lot of time and effort on finding or creating gifts, especially those intended for the sultan and his family. Even the handkerchief the sultan dropped in front of the girl with whom he chose to share his bed was considered gift-giving.

Gifts were not just confined to any particular holiday. Births and weddings naturally included gift-giving, and when it was a sultan’s daughter marrying, the more sumptuous the gift the better. What may seem a bit strange today is that the bride and groom were expected to provide presents as well. One of the grandest gifts of all was the Ottoman Golden Festival Throne. When Ibrahim Pasha, the governor of Egypt, married Sultan Murad III’s daughter in 1586, he presented the throne to the sultan as a gift. It was made of walnut wood and was covered with golden plaques. It weighed 250 kg and was encrusted with 954 chrysolites.

Gift-giving had an important role in diplomacy and had to be carried out with the greatest of care and consideration. Such gifts between rulers could be an insult if the value was little or the choice inappropriate. Holy relics made suitable gifts from the 16th to the 19th centuries, several of which are still on display at Topkapı Palace. Scientific treatises, literary texts, illuminated manuscripts, objects d’art and innovative craftsmanship and technology were also appropriate.

Gift-giving between the Ottomans and foreign countries depended on the circumstances and time as it did with all countries. Queen Elizabeth I sent an organ to Sultan Mehmed III along with organ master Thomas Dallam in 1599. Over the years time-pieces were popular as well and a large collection of them is to be found in various Ottoman palaces. The same can be said for weapons, especially guns, many of which were beautifully decorated with inlaid mother-of-pearl or studded with jewels.

Kaiser Wilhelm II came in person to Istanbul in 1889, possibly out of curiosity but mostly to ensure relations between Germany and the Ottoman Empire. His gifts were comprised of “a jewel-encrusted gold pocket watch decorated with a miniature portrait of himself, a large rococo clock, two nine-branch candelabra, and, a little later on, one of his personal state-of-the-art revolvers, complete with jewel-encrusted ivory handle.” In return, Sultan Abdülhamid II provided a number of jeweled items and “the entire elaborately carved decorative limestone facade of the eighth century Umayyad Caliphate Palace of Mshatta [today’s Jordan].”

Sultans and members of the imperial family also gave gifts to foreign dignitaries. We know that every ambassador received a very valuable caftan upon being given an audience by the sultan. Other gifts included towels, pajamas, turbans and even tiaras.

Merchants trying to obtain orders were also expected to provide gifts although today we might find that rather strange. One had only to note the many beautiful pieces on display during the recent exhibition at Topkapı Palace of items from the Kremlin to see many different pieces gifted to the Tsars by Greek businessmen from Istanbul.

Jewelers certainly had plenty of work in those days.