Fitch and the crane

I had no idea what the ratings agency Fitch could have in common with a crane.

Soon

after Chief EU negotiator Egemen Bağış tweeted,

at a meeting about the EU’s Leonardo

da Vinci education program, that “he was driving a truck called Leonardo da

Vinci” (vinç is the Turkish word for crane), Turkish daily Sabah, whose

anti-Semitic rhetoric I discussed in a previous column

and blog

posts,

disclosed “Fitch’s code”, obviously inspired by the Dan

Brown bestseller.

Perhaps

taking cues from Economy Minister Zafer Çağlayan, who recently urged us “to

look at who owns Fitch”, Sabah took on Fitch as part of its series about

the ratings agencies, exposing that its two shareholders are members of Opus Dei and Illuminati. I had learned from Tom Hanks that the two are

bitter enemies, so it is great to know they have finally put aside their

differences.

Unlike

at the end of July, Çağlayan did not say this time that “Fitch

has done the Fitch thing”, a play on a Turkish swear word that sounds

similar to Fitch, but government officials reacted very strongly to the

decision to downgrade Turkey’s outlook for external debt from positive to

stable, thereby killing hopes of an upgrade to investment grade in the short

term.

According

to the ratings agency, the decision “reflects an increase in near-term risks to

macroeconomic stability as Turkey faces the challenge of reducing its large

current account deficit and above-target inflation rate against the background

of deterioration in the global economic and financing environment.”

Central Bank Governor

Erdem Başçı recently asked what it would take to convince the likes of me that

inflation would fall next year, and I will answer that question in next week’s

column. As for the current account deficit, last

week I explained the Turkish economy’s exposure to Eurozone woes by

pointing out the strong trade ties with the EU and the country’s huge external

financing requirement.

The

more sophisticated among the government supporters note, while acknowledging

these vulnerabilities, that markets are judges in a beauty

contest, and despite the odd pimple, Turkey is still more beautiful than

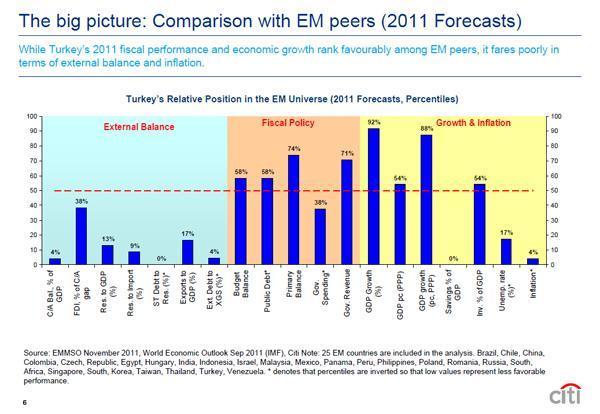

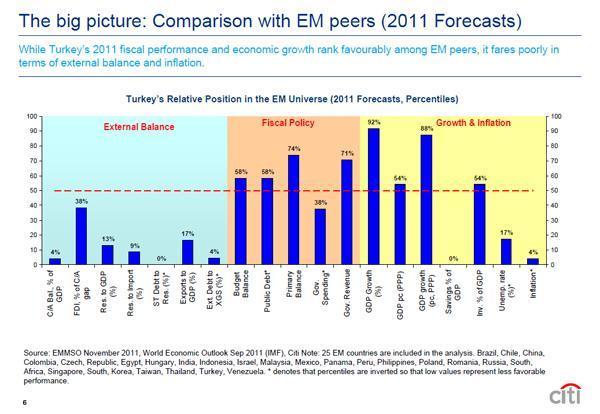

its emerging market, or EM, peers. A

recent chart prepared by Citi Turkey economists takes on this claim by looking

at how Turkey compares to 24 other EMs in terms of a number of indicators of

external balance, fiscal policy, growth and inflation.

Figures

for this year reveal that Turkey “fares poorly in terms of external balance and

inflation”. The former is illustrated with another chart, this one from Citi’s

global team, which shows Turkey as the country with the highest external

vulnerability.

I

am sure you’d find Knights

Templar, Freemasons

and the like among Citi’s major shareholders, but Goldman Sachs reaches similar

conclusions. They show

that Eastern European countries are exposed most to Eurozone woes, and

among these, Turkey and CE-3 (Czech Republic, Hungary & Poland) look

especially vulnerable. This might explain why Başçı was comparing the lira to

the forint and the zloty during his recent presentation at the Ankara Chamber

of Industry.

But then again, Goldman Sachs is controlled by Jews.