Feb 28 coup unintentionally spawned AKP, says academic

ISTANBUL - Hürriyet Daily News

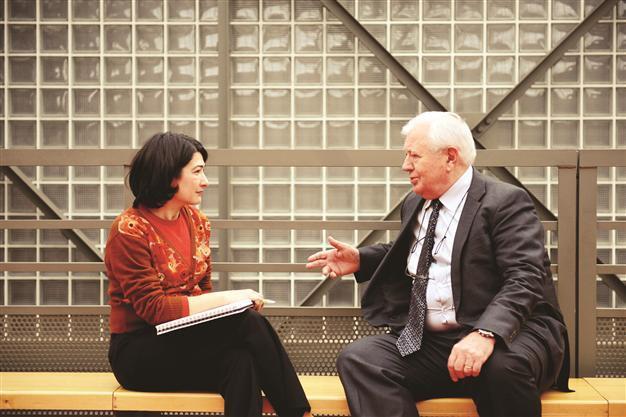

During the Cold War, the U.S., as the leader of the Atlantic Alliance, tolerated undemocratic domestic change in Turkey for fear of risking Turkey’s important contributions to NATO, according to İlter Turan. But times have changed and it would be a mistake to assume that U.S. policy toward Turkey and military interventions has remained stable in favor of the military, Turan told Daily News speaking at Bilgi University. DAILY NEWS photo, Emrah GÜREL

The emergence of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) is the most profound, if ironic, consequence of the military’s attempt to staunch increasing religiosity in Turkish society in 1997, according to a leading scholar.The military’s “post-modern coup” of Feb. 28, 1997, in which the army forced Turkey’s first Islamist government from office, “caused a major reorientation and transformation of the [governing] religious party,” Professor İlter Turan said. “The AKP is the most important unintended legacy of the intervention.”

During the Feb. 28 process, the traditional leadership of the main religious party was replaced by pragmatic people who merely sought to run an efficient government. “They emerged as victors, something that the generals did not intend,” Turan recently told the Hürriyet Daily News in an interview.

How would you summarize Feb. 28?

Feb. 28 was the last major intervention by the state elites into the doings of the elected elites. The

If the military had not

found receptive

elements in the

population, they would

not have been able to

implement the

policies they did.

This proved problematic, particularly for the military.

But there were also those among civilians who were concerned by the threat to

secularism. Did these concerns have a valid basis or was it exaggerated by the military’s propaganda?

There are court cases pending that there were some activities planned by certain agencies of the government to essentially present a religious threat that was not necessarily there. We don’t know enough about it to judge how true these allegations are.

But I would not be surprised if some part of state elite may have exercised some indiscretion in trying to persuade the public that there was a clear danger of a religious takeover of the state.

But there is no reason to suspect that the concern itself was not real. Some people were really concerned.

Some believe that the civilians that applauded the military should be considered guilty of having contributed to the Feb. 28 post-modern coup.

We are not talking about a crime but essentially a behavior whose morality may be questioned.

Some of these people seriously believed that there was a major threat facing the Turkish political system. They wanted to make certain that this threat was averted; they saw the military as the only [institution] capable of averting that threat.

Having said that, when power is exercised in an undemocratic fashion, many people see opportunities for themselves to advance their causes by ingratiating themselves with those that hold power. This is highly unethical behavior that is trying to capitalize on the monopoly of the power of the military and trying to manipulate the military for their personal ends. The moral responsibility is great and many people committed immoral acts that essentially extended support to the way military was doing things. I venture to say that if the military had not found these receptive elements in the population, they would not have been able to implement the policies they did.

But with the exception of people who actually committed real crimes defined according to the existing laws of the time, you cannot blame people for having done things legally. [But] you can certainly criticize them politically for what they did.

Part of the public should

stop thinking the best

defense for democracy

is the military. The best

defense is for citizens

to take an interest

in politics

So how should we deal with the responsibility of civilians in the Feb. 28?

If one were to identify a failure it may have been in the failure of elected politicians because they did not necessarily challenge what was happening. When you have elected politicians not challenging what’s happening, it becomes difficult for average citizens to say anything else. Civilian leadership, elected politicians, university rectors and the judiciary all failed. They did not defend democracy because the habit of thinking was mainly that the protection of the interest of the Turkish state was superior to any other concern they might have.

What is Feb. 28’s legacy for the Turkish political system?

It caused a major reorientation and transformation of the [governing] religious party. The traditional leadership was replaced by a group of pragmatic men who were interested in running an efficient government. They emerged as victors, something that the generals did not intend. The AKP is the most important unintended legacy of the intervention.

Some argue that political elites backed down and thus prevented an actual military coup.

You could equally argue that had the militarily encountered more determined resistance from the elected politicians, they would have revised their goals.

What’s your view; was the military bluffing?

The military would have reconsidered what they were doing. We have to remember that Turkey is not a country on the moon but is part of the international system. We are talking about a period when the Cold War had come to an end and where the democratization of the entire world was on the agenda and where Turkey was closely connected to centers which were promoters of democratic governance all over the world, such as the United States and the European Union. The Turkish economy was becoming increasingly integrated into the world economic system, so the cost of the military intervention would have been extremely high, and I am sure the military would have been able to judge this and revise their thinking because it was no longer possible for a non-elected rigid center to run Turkish society, whether civilian or military.

So what the military was probably able to see was not well-read by the political elites.

We have to keep in mind that the military is not as homogeneous an organization as we think it is. It has become all the more evident in later years that different commanders have different opinions on how the military should behave in politics. I would venture that probably a considerable number of high-ranking officers would have appreciated the unacceptable consequences of military intervention for Turkey.

So politicians were probably not able to read the international atmosphere at that time.

I would venture to say that, until recently, Turkish politics was so inward-looking that our politicians had not been particularly capable of reading what was going on in the world. Even today it is a problem.

But the Turkish public has a strong conviction that these coups were supported by the U.S.

During the Cold War, it was true that the U.S., as the leader of the Atlantic Alliance, tolerated undemocratic domestic change in Turkey for fear of risking Turkey’s important contributions to NATO. But we are now talking about long after the end of the Cold War. The U.S. would no longer be able to come out openly and essentially support a non-democratic government. The times had changed. I think it would be a mistake to assume that U.S. policy toward Turkey and military interventions has remained stable in favor of the military. That’s not the case. During the Cold War, European allies did not necessarily do much about military interventions in Turkey either. They were not nearly as tolerant toward the Greek generals because the Greek contribution to Atlantic security was not as big.

What was the U.S. attitude to Feb. 28?

In the interests of not severing the relationship, [there was no] strong unfavorable commentary emanating from the U.S. [That might be] interpreted as tacit approval, but I am not so sure that it was.

What do you think about the current process, is it a healthy one?

We should see Feb. 28 as a degeneration of the democratic process, and we should make sure we understand what went wrong and what we need to do to correct it. As for trials, I am curious as to how these would turn out because the argument made by [recently arrested suspect Gen. Çevik] Bir and his friends is understandable. They say the law gave us the power and the obligation to do these things, we worked with the Cabinet, and we did not exceed anything that the government told us.

I think what the general did was wrong. We should make sure that it does not happen again. But if we try to treat it as a court problem, we must be sure that these gentlemen actually violated a law that was in existence at that time and that they committed criminal acts. This will put an excessive burden on the judiciary.

If they say no crimes were committed, there will be a reaction, but if they say crimes were committed, it will be difficult to prove what the crime was. Our state establishment gives room to the military for this sort of behavior. So we have to change our legal system that makes this possible and modify our thinking. A segment of the Turkish public needs to stop thinking that the best defense for Turkish democracy is the military. The best defense is for citizens to take an interest in politics and defend their ideas. The democratic process does not allow lazy citizens to criticize the government and turn to the military and tell the army that they need to do something about it.

WHO IS İLTER TURAN?

Turan was president of the Turkish Political Science Association from 2000 to 2009 and also served as vice president of the International Political Science Association from 2000 to 2006. He was also the program chair of the 21st World Congress of Political Science in Santiago, Chile, in July 2009.

He is the chairman of the board of the Health and Education Foundation and serves on the board of several foundations and corporations. He is widely published in English and Turkish on comparative politics, Turkish politics and foreign policy. His recent writings have focused on the domestic and international politics of water, the Turkish Parliament and its members, as well as Turkish political parties.