Farewell my baby-john

Unless the polls are way off, Supreme Leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will have become Turkey’s first president elected by the public when you read this column today.

Unless the polls are way off, Supreme Leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan will have become Turkey’s first president elected by the public when you read this column today.I am leaving the political consequences of his victory to political commentators. Suffice it to say I agree with fellow Hürriyet Daily News columnist Mustafa Akyol and political risk consultant Cenk Sidar, two people usually with very different views, that we are prone to much more tension. Instead, I would like to concentrate on the economic consequences of his presidency.

Are we likely to see sounder economic management once Erdoğan gets his Precious? Hardly! First of all, becoming a ceremonial president is not enough for Erdoğan. While he has said he will make use of the clause in the Constitution that allows the president to chair Cabinet meetings as he deems necessary, he will also try to get enough votes in the 2015 general elections to change the Constitution to legalize his rule.

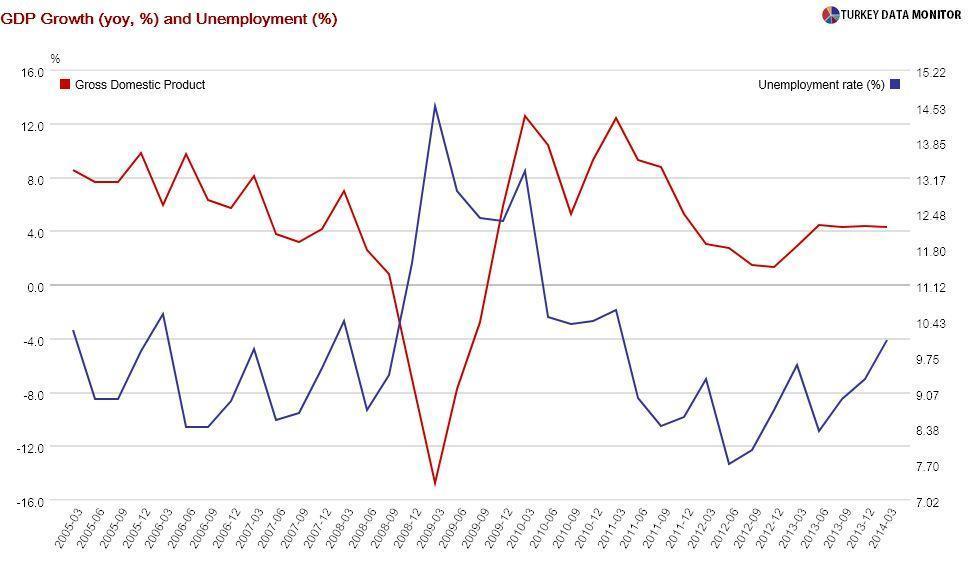

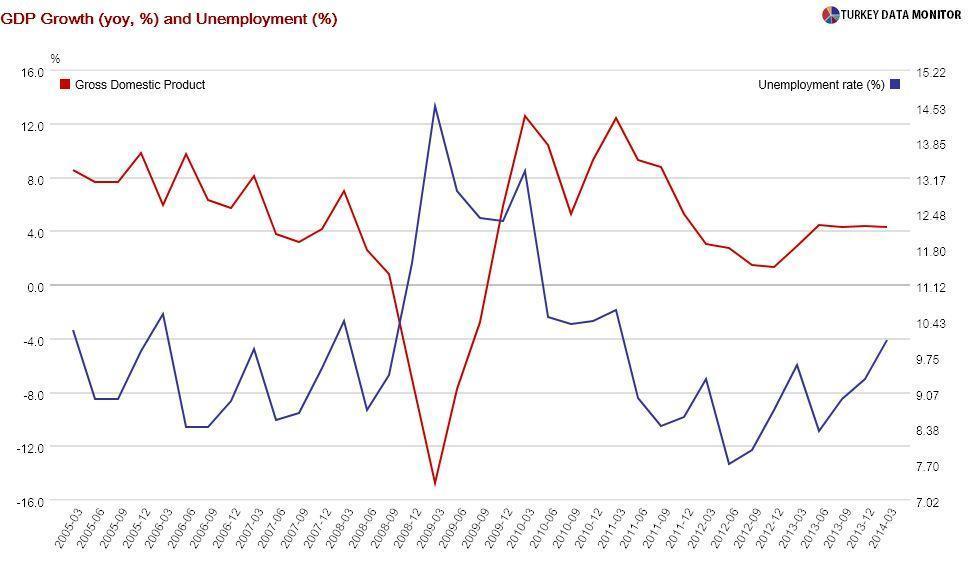

Economics is the main factor in Turkish elections. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) received its lowest votes after coming to power in the 2009 local elections, which coincided with growth bottoming out and unemployment peaking. With the latest indicators hinting at a slowdown, Erdoğan will pressure the Central Bank for lower interest rates. Economy czar Ali Babacan will probably not be there to back Governor Erdem Başçı.

Babacan was expected to leave in 2015 because of the AKP’s internal rules anyway, but he may be left out of the new Cabinet this month. Green in politics and economic policymaking when he became economy minister in 2002 at the age of 35, Babacan was called “baby-john” by the markets. Other than a brief stint as minister of foreign affairs, he has been in charge of the economy for a decade. During that time, he managed to gain investors’ confidence.

I have had the pleasure of listening to him live on many occasions and I was impressed by his ability to sugarcoat the AKP’s economic slip-ups. He almost made me believe once, even though I knew better, that Turkey was implementing structural reforms. But lately, he has been sounding increasingly like an opposition party politician by lamenting on the delay in structural reforms, as well as the lack of democracy.

Pro-AKP media has already accused him of being a Gülenist, but I knew Babacan’s time was up when he was refuted by Erdoğan’s chief economic adviser Brave Cloud last week. Cloud stated on Aug. 6 that state-owned Ziraat Bank had no plans to buy beleaguered Bank Asya, even though Babacan had confirmed acquisition talks earlier in the day. Bravie would not have dared to cross paths with the economy czar without the Supreme Leader’s blessing. Markets have smelled blood as well: A fund in town this week would like to meet up with Cloud.

Babacan is not just vital to soothe investors. Without Babacan, there won’t be anyone close to Erdoğan who can convince him to do the right thing, especially if former President Abdullah Gül is kept away. If capital flows to Turkey dry up and the Turkish Lira depreciates, who will spend hours convincing Erdoğan the need for an emergency rate hike? Who will persuade him that without reforms, Turkey cannot grow in the absence of external financing?

But maybe Babacan should leave. According to Niccolò Machiavelli, “the first impression one gets of a ruler and his brains is from seeing the men he has about him.” Investors were getting all the wrong impressions about Erdoğan from Babacan. They are sure to get a more accurate picture from Brave Cloud.