Erdoğan: Less European, but more Islamist

İLKER BİRBİL/KORAY ÇALIŞKAN

Having accused the New York Times of being a “shameless, nefarious and villainous newspaper adept at publishing lies,” Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan would be surprised to read thousands of bytes of positive coverage in the same newspaper. An analysis of the 1.2 million words, which make up the 1,472 news items and 44 editorials that the New York Times has published about him over the past 10 years shows a substantive change, not in the tone of the coverage, but in the ways in which Mr. Erdoğan himself conducts politics.

Having accused the New York Times of being a “shameless, nefarious and villainous newspaper adept at publishing lies,” Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan would be surprised to read thousands of bytes of positive coverage in the same newspaper. An analysis of the 1.2 million words, which make up the 1,472 news items and 44 editorials that the New York Times has published about him over the past 10 years shows a substantive change, not in the tone of the coverage, but in the ways in which Mr. Erdoğan himself conducts politics.Our research is based on the data collected through the application programming interface provided by the New York Times. Eliminating broken links, blogs and unrelated articles, we isolated the entire universe of relevant coverage in the newspaper’s pages between Jan. 1, 2004, and Oct. 10, 2014. With the help of recent text analysis tools, we evaluated the sentiment score of this coverage by using SentiWordNet, a lexical resource that scientists use for opinion mining. The results show a clear picture contradicting his accusations.

Ten years ago, the western media saw Mr. Erdoğan as a champion of democratization. A great majority of the Turkish press and various political actors agreed with this assessment. Even Erdoğan’s liberal and left-wing critics rallied behind his series of constitutional amendments, summarizing their position with the now infamous phrase “not enough, but yes.”

Much has changed since then. The Gezi Uprising not only took the lives of eight young demonstrators, but also damaged Mr. Erdoğan’s charisma within the country. Istanbul’s Marmara University, in a move to prevent student protests, had to cancel classes on Oct. 13, 2014 so that Mr. Erdoğan could deliver a talk during the academic year’s opening ceremony without interruption.

Mr. Erdoğan closed down Twitter, banned YouTube on multiple occasions, took bold steps to control the media and the judiciary, and has shied away from openly taking a stance against Islamic extremism in Syria and Iraq—this has resulted in a colossal and rapid decline of his popularity all over the world.

Despite the speed of his decline in popularity, the New York Times largely continued to refrain from negative coverage about Mr. Erdoğan. A longitudinal statistical analysis of the relevant news coverage and editorials demonstrates only a slight increase in negative sentiment toward Turkey’s president.

Analysis suggest that the New York Times’ take displayed journalistic objectivity and no sudden change of heart.

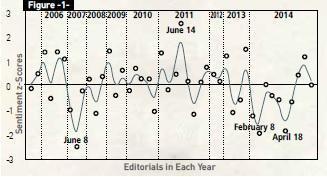

Figure 1: Sentiment z-scores of relevant editorials

The peak in Figure 1 reflects a very positive editorial about Mr. Erdoğan’s victory in the 2011 elections. One of the lowest points occurred in April 2014, when Mr. Erdoğan called Twitter “the worst menace to society.” This was also around the time when the editorial board pointed out the danger in his accusations against “Zionist and other European interest rate lobby operations in Turkey,” which were intended to divert public attention from the corruption investigations that forced four ministers to resign from his Cabinet.

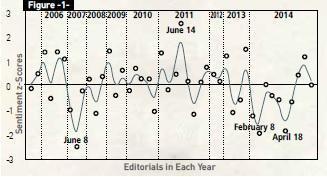

Figure 2: Sentiment z-scores of all coverage, including op-eds and editorials

Furthermore, the occasional negative sentiment displayed in the earlier years does not necessarily mean the statements were against Mr. Erdoğan. On the contrary, when the Turkish Supreme Court attempted to ban his political party, the New York Times depicted this move as a clear threat to democracy and critiqued not Mr. Erdoğan, but the position that Turkey’s establishment held against him.

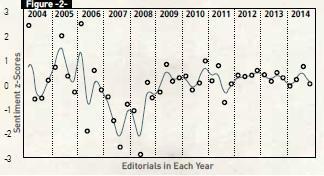

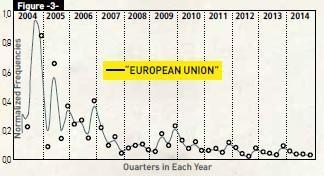

Yet, this balanced coverage cannot conceal three important changes regarding Mr. Erdoğan’s new image as seen in the pages of the New York Times. An analysis of the words “Erdoğan” and “European Union,” as summarized in Figure 3, suggests he has been increasingly less associated with the European Union. Ten years ago, the words “Erdoğan” and “European Union” together appeared 10 times more often than they did in the past four years. (The scores in Figures 3-5 are reported after dividing them with the highest score for normalization. Note that the data for the last quarter of 2014 is rather limited.)

Figure 3: Association of Erdoğan with Europe

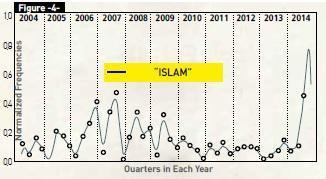

As his association with Europe has declined, we can observe a sharp increase in Mr. Erdoğan’s perceived fellowship with Islamism and authoritarianism. Ten years ago, Mr. Erdoğan was more often linked with Europe than with Islamism. Now there is a sharp decline in his connection with Europe and a phenomenal increase in his association with Islamism. Figure 4 clearly displays this change.

Figure 4: Association of Erdoğan with Islamism

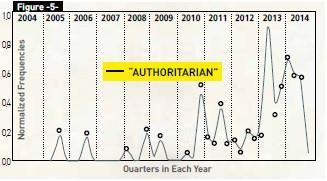

The emergence and demise of the Gezi Uprising and the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in the politics of the Middle East coincided with an interesting twist: once a champion of democracy, Mr. Erdoğan is now associated with authoritarianism, and this association is growing exponentially, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Association of Erdoğan with authoritarianism

No authoritarian leader can survive in the world of democracy. If Mr. Erdoğan wishes for his coverage to return to the good old days of progress, the data suggest that, instead of attacking internationalist journalists, he needs to revise his international and domestic politics.

İlker Birbil is a professor of Industrial Engineering at Sabancı University.

Koray Çalışkan is an associate professor of political science at Boğaziçi University.