Delayed land register is never-ending epic in Greece

ATHENS - Reuters

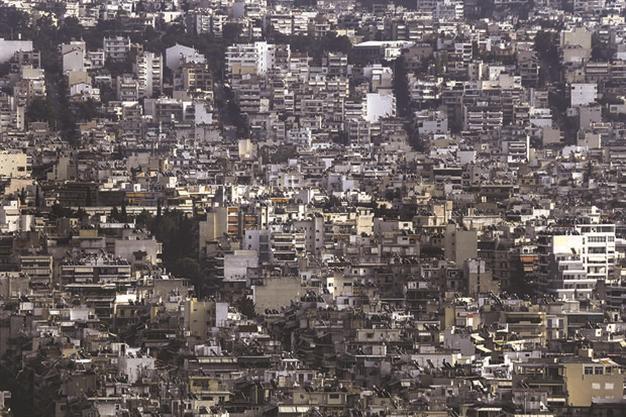

REUTERS photo

When Greece applied for its first international bailout in 2010, only two countries in Europe lacked a computerized register of land ownership and usage. Albania was the other.Experts from European Union (EU) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) identified the lack of legal certainty about property rights and land usage as a major barrier to investment, proper taxation and economic development.

Five years on, Greece is on its third EU/IMF bailout. Each of those programs has made a priority of completing a land register, known as a cadaster. Yet it is still less than half done despite spending hundreds of millions of euros with technical assistance from EU partners.

Meanwhile Albania, a far poorer Balkan neighbor that is still a distant candidate for EU membership, has leapfrogged Greece and implemented a digitized land registry and zoning map, even if some holes remain.

Greek newspapers call the never-ending epic of the cadaster, started in 1995 with EU funds that had to be returned to Brussels in 2003 because of misuse, “our national shame.”

It is a microcosm of everything that remains to be fixed in the country - bureaucracy, political patronage, competing layers of government, legal complexity, fiscal uncertainty, vested interests, cheating, tax evasion and opaque relations between the two biggest landowners - the state and the church.

The continued absence of a comprehensive land registry is one reason why a privatization program announced in 2011 and initially meant to raise 50 billion euros ($56.73 billion) over five years has netted a mere 3.1 billion euros to date.

Roughly half of deals so far have come from the sale or lease of state land, including a flagship plan to sell the disused Hellenikon airport site next to Athens which is still stalled.

The 50 billion euro goal was reaffirmed in the third bailout package agreed in August but stretched out over 30 years.

The state cannot sell its prime real estate while disputes fester in the courts about ownership, boundaries and zoning.

“We have to give investors certainty that whatever they get from the Greek state they can actually realize,” said Lila Tsitsogiannopoulou, executive director of the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund in charge of land privatization. “We still have a long way to go. We still have so many authorities.”

Illegal house owners’ union

The country even boasts a union of illegal house owners that campaigns to legalize their homes.

Michael Vlahakis a 60-year-old pensioner from Heraklion, the main city on Greece’s largest island Crete, is president of the “Residents Outside Town Planning” club, which he says represents some 45,000 illegal home owners on the island.

“Our club is unique in Greece, in Europe and probably in the whole planet because Greece is the only country in Europe that doesn’t have a cadaster,” he told Reuters in an interview.

“We still don’t know what is mountain, what is forest and what is a building or a house.”

About two-thirds of Greeks lived in the countryside until the 1960s, when a massive rural exodus began.

Now more than half live in the cities of Athens, Thessaloniki and Heraklion.

Vlahakis, who says he has built two illegal houses, one for himself and his wife, the other for his daughter, was invited to Athens four years ago to address lawmakers and ministers in parliament on the need to adapt town planning to reality.

“They haven’t done it since the mid-1980s despite the fact that Heraklion city has more than tripled in terms of houses and land since then,” he said, describing an upside-down urban development process.

“In Greece we build the houses first, then the roads, after that the infrastructure - waste system, electricity and water network - and at the end the sidewalks.”

Politicians, real estate developers and construction firms had all sabotaged the cadaster project to protect their interests, Vlahakis said.

According to Dimitris Rokos, director of planning and investment at the National Cadaster and Mapping Agency, just 25.3 percent of the country has been completely mapped, another 22 percent is in the works and contracts have yet to be awarded for just over 50 percent.

The agency has lost key staff such as the IT director and top legal experts to the private sector due to steep pay cuts under austerity measures imposed by Greece’s lenders. It also endured long months without a budget in the last five years.

It remains shackled by being a public utility company under the authority of the environment ministry, even though it is partly self-financing. The chairmanship has changed four times in as many years, mirroring successive governments, including twice this year when a hard left minister was appointed, then sacked.

Originally due to have been completed in 2008, the cadaster has an overall budget of 1.2 billion euros and is now supposed to be completed in 2020.

That seems wildly optimistic, but Rokos said the deadline could still be achieved if the agency were given greater financial and management autonomy to run more efficiently.

“It is still realistic if the government takes some basic strategic decisions by the end of the year,” he said.

Some of the problems are the legacy of history. Greece was part of the Ottoman Empire for centuries until 1830 and has since been scarred by wars, occupation and mass migration.

Most land transaction records in this nation of 11 million people, sprawling over 132,000 square km, are still handwritten in ledgers held by local registrars.

There are no title deeds for land in some parts of the country, and any area for which documents proving private ownership are not available from 1883 onwards is deemed to be state land, causing endless legal disputes.

Compounding the problem, resolving business disputes through the courts takes nearly three times as long in Greece as the average in members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a rich countries’ club.

The Greek Orthodox Church has no central land registry, forcing the state cadaster agency to deal with individual monasteries or diocese to try to establish land ownership and delineate boundaries.

Documents may be two centuries old and define the limits of properties with reference to landmarks that no longer exist, or using fuzzy phrases such as “500 paces from the olive tree” or “five stone throws in this direction”.

Roughly 60 percent of the country is officially designated as forest, protected by the Greek constitution from economic exploitation. The perimeters of forests are largely delineated by aerial photographs taken shortly after World War Two.