BLOG: The legacy of the Gezi protests, from the streets to government offices

Delphine Rodrik

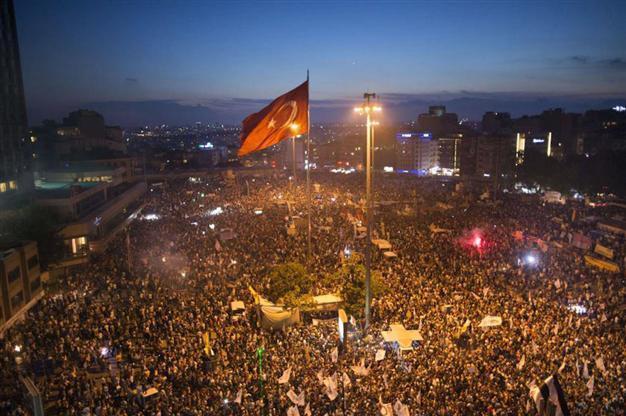

In June of 2013, amid rising clouds of tear gas, many in Turkey were increasingly optimistic. The protestors who had taken part in the Gezi movement, spiraling outward from Taksim Square, from social media onto the streets, were convinced that voicing their collective dissent would bring about change. As important as the many demands articulated by Taksim Dayanışması, the umbrella organization of the protests, was the protestors’ determination to be heard. But over a year later, many remain uncertain that they were. The drive for sustained dialogue and action has faded into disillusion. Were the Gezi Park protests a “random social explosion” as one protestor now dubs it, or a sustained shift in Turkish politics?

In June of 2013, amid rising clouds of tear gas, many in Turkey were increasingly optimistic. The protestors who had taken part in the Gezi movement, spiraling outward from Taksim Square, from social media onto the streets, were convinced that voicing their collective dissent would bring about change. As important as the many demands articulated by Taksim Dayanışması, the umbrella organization of the protests, was the protestors’ determination to be heard. But over a year later, many remain uncertain that they were. The drive for sustained dialogue and action has faded into disillusion. Were the Gezi Park protests a “random social explosion” as one protestor now dubs it, or a sustained shift in Turkish politics? Most of the diverse protesters I interviewed that June stressed that the protests were remolding Turkey’s public sphere not only politically but also socially. The protestors were a “fragmented, amalgamated, mixed, diffused front,” one onlooker described as the protests continued. Gezi, at its center, brought those of different backgrounds, ages, and politics into a common space, a public forum where all opinions could be shared. By the numbers, Turkey recorded 5,532 protests organized in 112 days, approximating 3.6 million people who had attended, according to a report by the International Federation for Human Rights. “It was time to raise our voice, but we didn’t know how many more were out there thinking like us,” said Merve, a protestor who was 26 at the time. “Now we’ve seen how many we are.”

Elif, a Gezi protestor who had witnessed two coups in her lifetime, discussed a palpable change in the air. “Our parents raised us with fear and despair, because they couldn’t … change things in a better way for our country,” she said, describing a common tendency to stay out of politics. “We thought that everything would go this way forever and probably worse.” Gezi, however, was changing this long-cemented outlook: Those directing the movement were “not talking with political or philosophical references like their parents.”

Protestors already recognized a challenging road ahead of them, but one that still led to change. “I don’t feel the intuition to go out into the streets and protest,” a protestor named Serdar told me two weeks after he had been recovering from tear gas inside Dolmabahçe Mosque. “But I have this deep urge to go out and do things that will make this country and my community better in the long term.”

The enthusiasm of these protestors proved difficult to sustain on this scale, however. Elif now says she and many others have confronted “a sort of bitter reality” in which Gezi’s ideals are not present. Many protesters have since faced trials for their involvement. But it has become difficult to define exactly what Gezi is, she says, and whether it has left any legacy at all. Merve, too, says recent political developments in the country have now left her feeling “powerless” to realize change. “Gezi was beautiful; it was unity,” she reminisces. But she believes it is “too late” for many concrete effects to take hold.

Some, like Elif, say social media outlets on the Internet still provide a place to gather and exchange ideas. But Gezi participants understand that dissent online, and even on the streets, is not enough for results. Various initiatives, such as citizen journalism projects, have evolved out of the groups involved with last year’s protests, though they are not backed by a similarly massive and united front. Graffiti and posters still speak on Istanbul’s streets, most of it advertisements for parties and political groups, but not necessarily in conversation with each other. On Istiklal, the site of much of last year’s action, it’s still common to see smaller protests and sit-ins and occasionally marches, framed by much larger crowds of on-guard police squads.

If Gezi hasn’t yet achieved tangible outcomes in the eyes of protesters, it seems to have done so from the government’s perspective. A Sept. 10 law increased the censorship powers of the country’s Telecommunications Directorate, which works closely with the government on Internet surveillance. More recently, a Sept. 27 government decree stressed that student in public schools cannot wear clothing that bears political symbols, dye their hair, have tattoos and piercings and grow mustaches or beards, among other restrictions. Beyond simply establishing a clear limit on personal freedoms, both these laws point to a shrinking space in which one can express individuality and voice opinion, regardless of content and location. On Sept. 29 Human Rights Watch reported “increasing intolerance of political opposition, public protests and critical media” on behalf of the government.

“[Gezi] raised massive awareness,” Merve says now, citing one definite outcome of the protests so far, “and suddenly everybody kind of woke up.” Although Gezi’s legacy, floating uncertainly in the background of politics today, has not achieved many of the protestors’ stated goals, one certain change is clear: That Turkey’s many disparate groups are capable of speaking aloud, and at once, has come to the forefront of public consciousness. For now it is the government that has acted more visibly on the increasingly apparent diversity of opinion, fearing the possibility of protest online, in the streets and in schools.