Being an Armenian today in Istanbul (2)

BELGİN AKALTAN - belgin.akaltan@hdn.com.tr

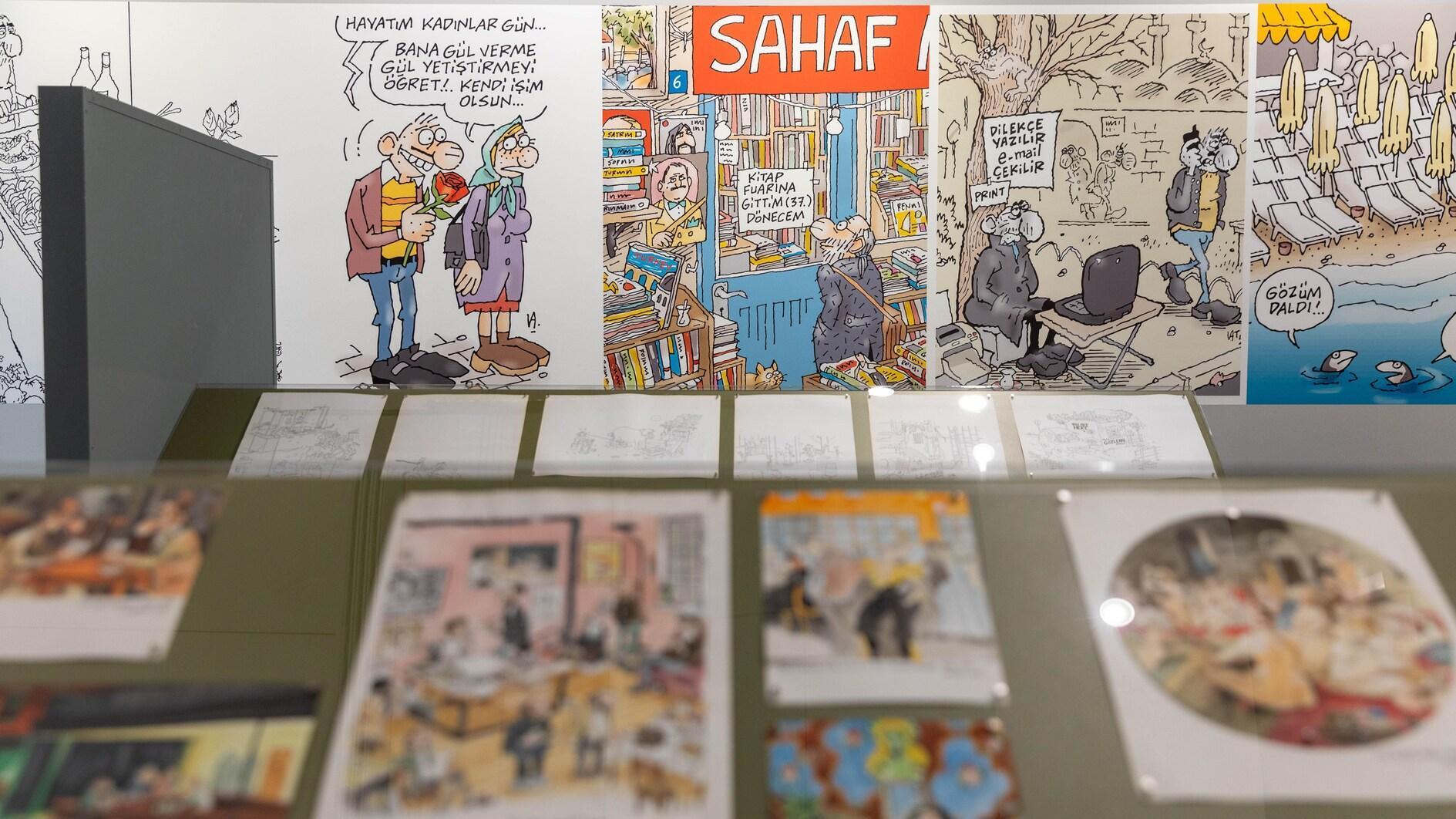

An Armenian wedding in the 1950s.

Continuing from last week, my last set of questions to my Armenian acquaintances was “Are you thinking of leaving? What makes you stay? What do you want this place to be like?”Talking about her school years, my colleague Vercihan Ziflioğlu said that for both her Turkish and Armenian teachers, “thinking and questioning” was the only issue that was never acceptable. They agreed only on this matter.

“They wanted unquestioning little brains, whereas I, even from that age, was questioning. My path as an individual was not very easy. A father with a French education, a freedom-loving mother, and a ‘Vercihan’ just back from France, it was obvious that my journey would not be easy in this land where I belong. There is, of course, also ‘being Armenian,’ which means ‘being different.’”

“I was interested in literature. When I brought Nazım Hikmet books to school one day, they wanted me to take these books out of the school immediately. I could not understand. On the one hand, I was asked to take Nazım Hikmet out of school; on the other hand, all the other landmark writers in the Armenian literature who I loved were said, in class, to have died of ‘tuberculosis.’ One day, when I asked why all of the writers had died of tuberculosis and how such a coincidence was possible, just like the day I brought Nazım’s book to school, I was asked to go home early and warned not to ask any questions on this matter. This is because all of them had lost their lives in the tragic events of 1915.

“It was the Nazıms and Orhan Velis and Armenian writers who died of ‘tuberculosis’ who have shaped the ‘Vercihan’ of today. Despite all the bans and impositions, I have learned to question. Instead of getting stuck at the troubles that society went through, I searched for new roads. I have witnessed the pain of other people in many different countries of the world. I learned that pain should not shape the future, but I also did not deny the pain of my ancestors.

“You ask me if I want to leave. Even asking this question means you actually perceive me as ‘the other.’ If one day I decide to go to any other country, be sure that I will never lose my ties with Istanbul and Anatolia. I would be here at every opportunity.

“As a woman, I want to be able to sit in an ordinary café without being the target of some strange stares. I should be able to, once in a thousand years, to stay alone and order wine for myself … I want a more modern, free Istanbul that stands up to its identity.

“My grandparents used to prepare themselves for one week before strolling down İstiklal Avenue. They would put on their gloves and hats and look in the mirror. Women would do their hair, put on their best clothes. Of course, times have changed; we cannot be like them, but I would like to live in that beautiful Istanbul with its cafés and the pastry shops they told us about.

Meanwhile, the young publicist, S., said Istanbul truly is a very beautiful city. “I believe we should really appreciate it. I have traveled a lot and when I talk to people and tell them I live in Istanbul, I see the spark in their eyes. I wish this city was a place where women and men live under equal conditions, where women’s purses are not snatched, where women are not murdered by the dozen every day.

“My ancestors were born here. We can trace back several generations, all born and raised here. I see this place as my country. I am not thinking of leaving because I feel that I belong here. Even though we may experience unpleasant situations from time to time, we have never thought of leaving our country as a family. Our wish is to live in a country where everybody is able to defend their ideas freely. This is not for minorities only; this is for all the people living in Turkey.”

Aslin Aslanoğlu also said that even though she has some concerns, she would not think of leaving her country. “Frankly, if an unwanted act or incident happened to me, I would not generalize it to all my non-Armenian friends. I would want all my non-Armenian friends to approach me like that too. As a result, I have very strong friendships, a life I have formed for myself. Absolutely, definitely I am staying here because I love my country. This is the only reason.

“Even though I have listened to certain unpleasant memories from my family about those times when they migrated from Anatolia to Istanbul and about the rural environment before that, I have also listened to stories involving very strong Turkish-Armenian relations. I have never acted with fanatic feelings.

“I have to add that I wish not only the city I live in, Istanbul, but the entire country should be a place where the rights of minorities are embraced; and equal circumstances, as equal as they can be, are provided for all minorities. I do not like using the word "minority," but this concept should include not only Armenians but all other cultures, atheists, homosexuals and our handicapped citizens, all of our people who are seen as ‘the other.’”

belgin.akaltan@hdn.com.tr

https://twitter.com/belginakaltan

belgin.akaltan.com