An old Kyrgyz village in eastern Turkish town

WILCO VAN HERPEN

Situated at the foot of a mountain range in the middle of a plain, Uupamir’s view is almost surrealistic, fantastic and the dream of every painter or photographer. Wilco Van Herpen photo

As you might know there are a lot of minorities in Turkey. Not only do we have Kurds, Armenians, Greeks, Jews and Gypsies, but there are at least 100 or more other minorities living in this country.Think about Abkhazians, Chechens and Georgians. Having lived in Turkey for 13 years, I thought I had more or less an idea about the minorities living here – until I went to Lake Van.

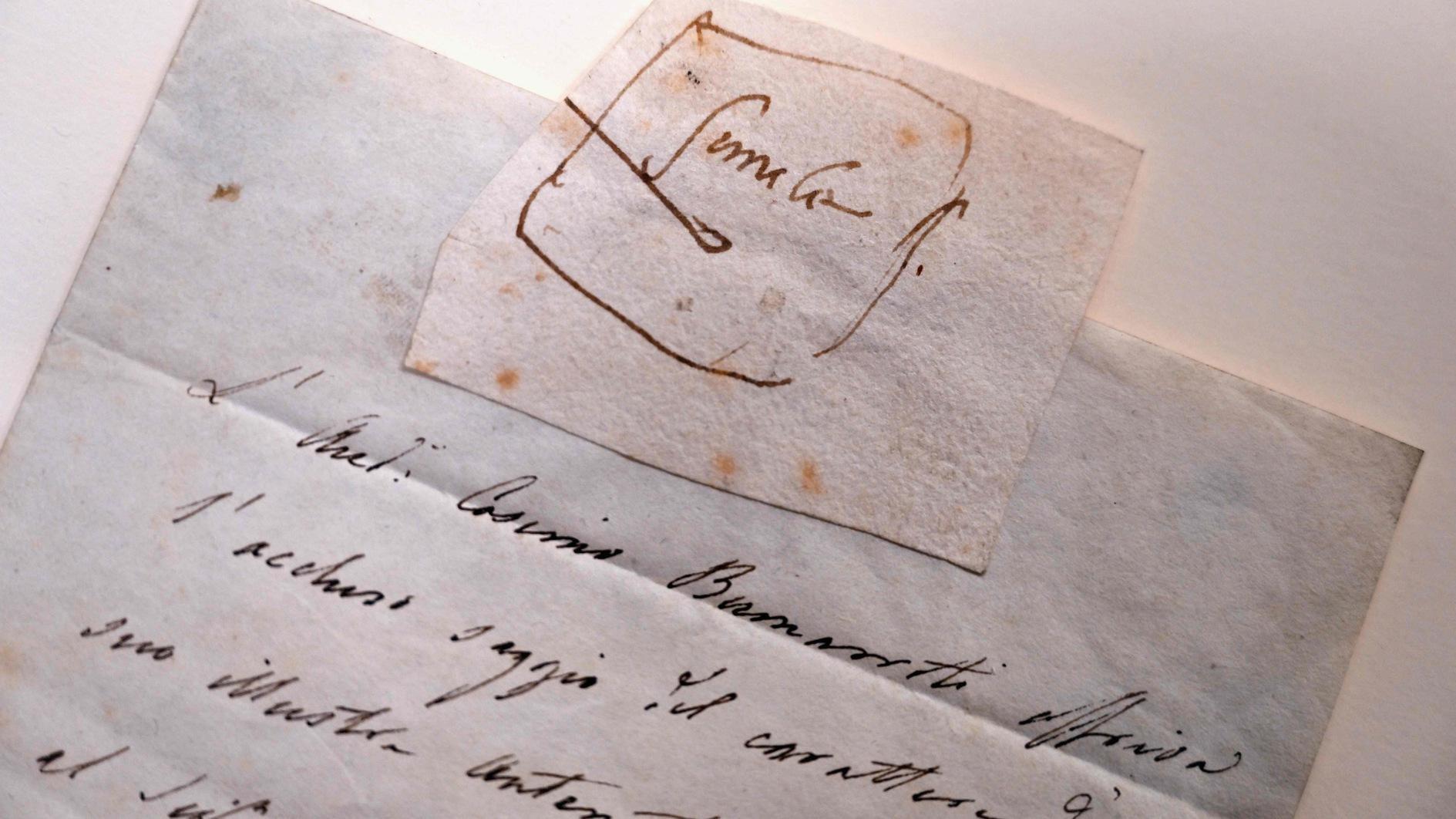

Near Erciş, which we all know by now because of the earthquake that hit the Van area, you can find a little village that is called Ulupamir. It was cold, very cold when I went to Ulupamir. Before I reached the village I got out of the car to have a look at what lay in front of me. The first thing that I noticed was the architecture. It was so different from the Turkish villages I know with its two-story-high long buildings, most of them built in a row next to each other. Straight roads, straight buildings – it reminded me of the prefabricated houses that I saw after the big earthquake in 1999.

By giving them a piece of land and building their houses, Turgut Özal wanted to create goodwill in the Turkic countries.

It was 1979 when the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan and forced the migration of a group of Kirgiz who were related to Hacı Rahmankul Kutlu Han. The group was sent to Pakistan, but they could not get used to the climate. It was far too hot for these people who were used to cold and harsh weather conditions of the mountains of Afghanistan. Temperatures could go down to even minus 35 degrees Celsius. In Pakistan it was hot for them, very hot. With temperatures rising up to 35 or even 40 degrees, people were suffering, and even a number of them passed away. They got in touch with the Turkish Embassy in Islamabad where they spoke about their problem. They thought the milder climate of Anadolu might be a better place to live, and it was Turkish President Kenan Evren who gave permission in 1982 for them to come to Turkey.

It was Turgut Özal who finally gave them a piece of land near Altındere. By giving them a piece of land and building their houses, Turgut Özal wanted to create goodwill in the Turkic countries. About 1,150 Kyrgyz moved and gave the new village the name Ulupamir, the name of a plateau in Afghanistan.

“Of course,” I thought, “what would a Kyrgyz village be without horses?” These people are born and raised on horses, and this tradition continues in Turkey as well.

After we finished our tea, Halil invited me for a walk through the village. It was a poor village, but everybody greeted me with friendly, smiling faces. Walking around, it became obvious to me what the people did for a living. Everywhere cows were walking around freely, and further away from the village I could see horses. “Of course,” I thought, “what would a Kyrgyz village be without horses?” These people are born and raised on horses, and this tradition continues in Turkey as well.

I took a bite, chewed and – a crispy sound, hard to chew, meat jumping around in my mouth, and this turned out to be the treat for guests.

Soon I was confronted with their traditions. They had specially prepared a meal for me, boiled head and meat of a sheep. First they served the eldest men of the village, then me and the rest of the people in the room. I was the lucky one to get the best part of the sheep: the ears. They were slightly burned and still “crispy” although boiled. I took a bite, chewed and – a crispy sound, hard to chew, meat jumping around in my mouth, and this turned out to be the treat for guests. As a chef I was not impressed with the taste, but as a guest I felt honored.