Art and artists in resistance

Emrah GÜLER

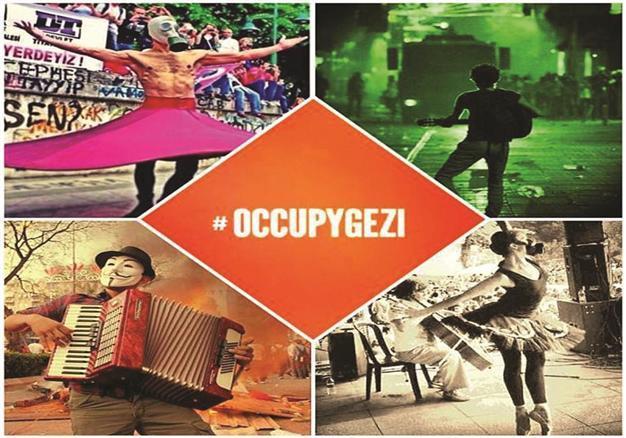

Many pictures, posters and videos depicting Gezi Park for the last 18 days have become a main attraction for the public.

The pictures and videos emerging from Gezi Park for the last 18 days are, among many other things, of great contradiction to the world trying to make sense of the protests and the clashes. The live coverage of police brutality to protesters and civilians with tear gas and water cannons alternate with scenes of peace and solidarity the next day, like a piano concerto in the park where thousands watched and applauded, including the riot police.German musician Davide Martello carried his piano to the center of the park on June 12 for a spontaneous performance with Turkish musician Yiğit Özatalay. The reaction was emotional, the feelings overwhelming, and the inspiration instant. Soon after, New York’s Zuccotti Park, home to the Occupy Wall Street movement, had its own baby piano.

As much as the protests against the Turkish government’s increasingly autocratic regime have been a source of angst and anxiety since its first days, it has also been a source of creativity and artistic inspiration. Protesters in social media have coined the term “disproportional wit” or “disproportional creativity” in an answer to the much-used term “disproportional violence” throughout the protests.

In the first days of the protests, pictures of graffiti, street art and posters put smiles across faces of those across their computers, surfing frantically on social media. Within the week, short films, animations and videos were circulating on social media. Some of these were the works of young, passionate amateurs, others products of professionals who contributed to the fight for democracy and freedoms through putting their talents in use.

If you visit the website capulcular.bandcamp.com, you’ll be able to listen to over 80 songs written, performed and recorded during these 18 days. Some of these songs are the covers of famous songs, like Sting’s “I’ll Be Watching You” or the rebel song from the musical “Les Misérables,” “Do You Hear the People Sing?” with the lyrics appropriate for the protests.

Do you hear the people sing?

But more than half of these songs are original songs, showing the diversity of the groups that have become part of the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul and across Turkey. You will listen to ethnic music of Laz and Alevi, classical Turkish music, rock, electro-pop, rap and anthems. Some of these songs were written and performed by acclaimed Turkish musicians like the momsy doyenne of Turkish pop, Nazan Öncel, and the rock heartthrobs Duman. Even the world-famous classical music pianist Fazıl Say, a recent target of the government’s crackdown on free speech, gave a concert in the Aegean city of İzmir with a pan, a popular tool of protest of those at their homes. Many filmmakers and actors have also become the voices of the resistance, going as far to set up a Filmmakers’ Tent in the colorful tent city in Gezi Park (to be broken by a raid by the police with tear gas last week). More than 700 film professionals, including directors like Özcan Alper, Fatih Akın and actors like Halit Ergenç and Cem Yılmaz, as well as 13 film associations, issued a call to the government last week, urging for “the termination of police violence, an end to threats of intervention and continuation of the dialogue.”

The concerned voices from the world of arts not only came from Turkey, but across the globe. The photo of a smiling Tilda Swinton, holding a paper that read, “Right now police is violently attacking citizens in Istanbul,” made the rounds in social media.

To reconcile (or not) with the art world

Other messages came from acclaimed musicians Patti Smith, Joan Baez, Roger Waters and Thom Yorke. An open letter to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan began with, “We, citizens of the world, are deeply saddened and concerned by the severe violence against citizens of Turkey by the Turkish police over the last couple of days in Turkish cities including Istanbul.” The letter was signed by American political critic and activist Noam Chomsky, British author Hanif Kureishi, actress and activist Susan Sarandon, British filmmaker Terry Gilliam, among other renowned names. The ruling Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) ignorance, disregard, and often disdain, for the arts have been a major concern of Turkey’s intellectuals, artists, and educated, urban citizens for some time now.

Two years ago, the prime minister had called well-known artist Mehmet Aksoy’s sculpture in Kars, a symbol of Turkish-Armenian friendship and reconciliation “a freak,” and asked for its demolition. Last year, Erdoğan condemned Turkish intellectuals of “despotic arrogance” after his daughter was insulted during the staging of a play. He threatened to cut state funding of country’s theaters, and he is making good of his word as the funding cuts for state theaters, ballet and opera are imminent.

So out of touch are Erdoğan and his colleagues from the AKP with the world of arts and culture, that their attempts to reach out and reconcile became a source of joke when he invited Necati Şaşmaz, the leading actor of the now-canceled ultra-nationalist TV series “Kurtlar Vadisi” (Valley of the Wolves), and the popular actress and diva Hülya Avşar, a public figure of indifference and insensitivity towards women’s issues and ethnic minorities. Şaşmaz’s lack of coherence and poor Turkish during a televised press statement following his meeting with the prime minister flooded Twitter with thousands of jokes. “World of translators and linguists unite,” said one tweet.

For Avşar’s meeting with Erdoğan, another tweet said it all, “Imagine Obama calling Kim Kardashian to the White House after a civil uprising.”