Put-off by offal?

Aylin Öney Tan - aylinoneytan@yahoo.com

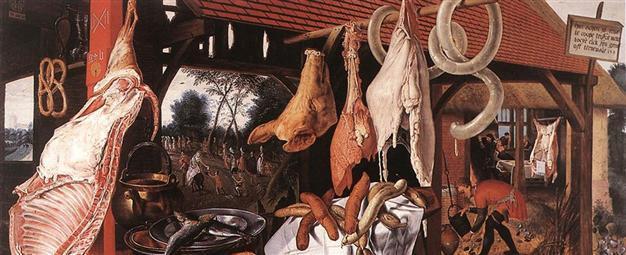

The food of the poor, but also considered a delicacy praised by the rich. An oxymoron it may seem, but that is usually the case for offal. This year the theme for the Oxford Symposium on Food & Cookery was offal. Organ meats, or offal, are generally perceived as the entrails of a butchered animal, but the symposium stretched the description way beyond that, covering all rejected and reclaimed foods including concepts like vegetable offal or a major global problem such as food waste. It was a thought-provoking and eye-opening weekend scrutinizing why we put some foods in our mouths with no hesitation, but remain doubtful of others, or even disgusted with the idea of eating certain foods.

The food of the poor, but also considered a delicacy praised by the rich. An oxymoron it may seem, but that is usually the case for offal. This year the theme for the Oxford Symposium on Food & Cookery was offal. Organ meats, or offal, are generally perceived as the entrails of a butchered animal, but the symposium stretched the description way beyond that, covering all rejected and reclaimed foods including concepts like vegetable offal or a major global problem such as food waste. It was a thought-provoking and eye-opening weekend scrutinizing why we put some foods in our mouths with no hesitation, but remain doubtful of others, or even disgusted with the idea of eating certain foods. The perception of offal varies greatly by nation, but also over time. When I was growing up children were fed all parts of animals with the belief that it was beneficial for their growth. Liver and spleens would make plenty of blood; brains would make one brainy; bone marrow was good for the bones; these were instant phrases said by grandmas to force-feed children reluctant to eat the questionable food on their plates. In later life the idea carried on: Tripe is good for your stomach after heavy drinking, testicles will act like Viagra for men, and so on… One thing was for sure, if you had a broken leg, then you had to devour lots of trotter soup, as the gelatin in the bone would act like a glue to fix your own bones.

Such beliefs start from the heart. Our affection for offal goes back to hunter-gatherer times. Hunters were entitled to have the heart of their hunt. There was a practical reason for the hunter to eat the heart and the liver, as these parts would be more prone to decay, whereas the rest of the animal could be transported back to the tribe, but the heart also had its symbolic context. The heart would make the hunter braver and it was unquestionably a reminder of the duality of life and death. According to Margaret Visser, who wonderfully dissected cannibalism in her colossal book “The Rituals of Dinner,” the human skull could well be the first-ever drinking vessel in history. Surely our combined fascination and disgust for offal has been very complicated ever since then…

Many cultures have mixed feelings about eating animal parts. The discarded food of one culture is indeed a delicacy and valued food of another. Fish innards are often discarded food in Western cultures, of course with the ultimate exception of caviar, but considered a delicacy in Japan. The Japanese approach to offal is very different from Western cultures, where there is no clear distinction between muscle meat and organ meat.

However, even eating muscle meat is a rather recent concept, much developed as a vehicle in a masculine, muscle-building capacity to make men stronger and be able to fight better. A couple of years ago, I remember reminding Claudia Roden, the president of the symposium, to eat as many jelly and trotter soups as she could when she had a broken leg. It was so interesting to see that offal cuisine, usually men’s fare in Japan, was becoming popular among young Japanese women as a source of collagen to have a beautiful and glowing completion. We clearly see that such beliefs keep repeating themselves, and offal cuisine is making a global comeback for various reasons, whether it be health benefits, curiosity, nostalgia, new trends, moral concerns or just for taste.

A week after the symposium, I still find myself thinking about various talks I had the chance to listen to. I had never been good about eating offal, but to admit I’m not a vegetarian. Now rethinking it, I’d rather not be a hunter but a gatherer. Foraging for your food picking wild greens seems to be much wiser way to go in this world of cutting throats. The outcome of the symposium for me was, as one keynote speaker put it, if we eat meat, better to eat it all! There is no point in discarding certain parts because it seems morally horrifying or disgusting. But disgust is one word we have to think about over and over again.

Mottainai is a Japanese concept that conveys a sense of regret for waste. In Japanese culture, with combined roots in Buddhism and Shintoism, discarding unwanted foods is seen as irreverent. My ultimate verdict, whether eating animals or not, is that we all have to develop a sense of mottainai and strongly detest wasting food! I cannot help but remember that we once had such a virtue in this country. Wasting food used to be religiously a sin, and morally unacceptable. Looking at the crowds cheering at the cutting of a young soldier’s throat, I realize that these masses will not find wasting food a sin. The real disgust should be about throwing away food that is still edible when half the world’s population is starving or fighting for it.