Erdoğan and the crisis of modern Turkey

William Armstrong - william.armstrong@hdn.com.tr

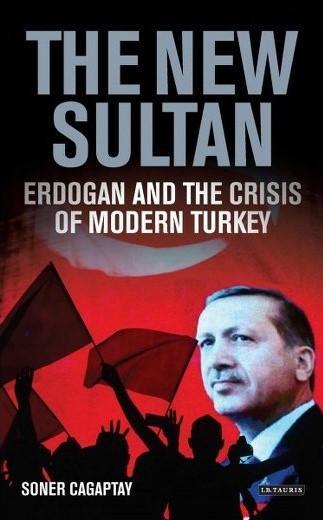

President Erdoğan delivers a speech during the opening ceremony of the 'July 15 Martyrs’ Monument' at the presidential complex in Ankara. AFP photo

‘The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey’ by Soner Çağaptay (IB Tauris, 240 pages, $25)In 2014 Soner Çağaptay published “The Rise of Turkey: The 21st Century’s First Muslim Power.” The book described Turkey as a dynamic force whose power had risen steadily over the past 20 years. It was not blind to the authoritarianism of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, but it optimistically argued that a stable and democratic future was still up for grabs.

Three years on Çağaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute think tank, appears to have had a change of heart. The title of his new book, “The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey,” gives a darker prognosis. Such a sharp about-face illustrates the deterioration of Turkey’s image abroad in recent years. It has also prompted ridicule of the conventional wisdom spouted by think tank pundits.

Three years on Çağaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute think tank, appears to have had a change of heart. The title of his new book, “The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey,” gives a darker prognosis. Such a sharp about-face illustrates the deterioration of Turkey’s image abroad in recent years. It has also prompted ridicule of the conventional wisdom spouted by think tank pundits. But the two books are not as simplistic as they appear at first glance. “The Rise of Turkey” was more skeptical about the country’s direction than its title suggested. “The New Sultan” pulls no punches in condemning Erdoğan’s policies, but it also gives a sensitive background context to his life and political upbringing. It does not make the reader any more optimistic.

The book sketches Erdoğan’s upbringing in the tough Istanbul district of Kasımpaşa. The son of a city ferryboat worker who migrated from Anatolia, as a boy Erdoğan sold simits on the streets and attended a conservative religious imam-hatip school. His rugged upbringing can still be seen in his mannerisms and speech today, appealing to many ordinary Turks proud that “he is one of us.”

Çağaptay charts how Erdoğan started out among nationalist Islamists in student politics of the 1970s. It was a turbulent decade in Turkey, as left-wing and right-wing groups waged bloody turf wars across the country. Cold War political Islam was defined by staunch anti-Communism and scepticism about the capitalist West, believing that both were stoking social and political turmoil.

Political Islam was inadvertently helped by neoliberal economic measures and the official “Turkish-Islamic synthesis” ideology imposed after the 1980 military coup. Erdoğan rose gradually through the ranks of Islamist politics through the 1980s and his breakthrough came when he was elected Istanbul mayor in 1994. His municipal administration earned a reputation for pious competence, but in 1999 he was barred from politics and jailed after delivering a rabble rousing religious poem at a public rally. The ban was lifted and he became prime minister in 2003 after the new Justice and Development Party (AKP) entered office.

In the AKP’s early years, optimists praised its apparent commitment to Turkey’s EU membership bid, liberal economic measures, and commitment to challenging the political influence of the military (often simplistically characterized as a “secular elite”). It also expanded health services and infrastructure, winning the hearts of many long-marginalized voters. The party included traditional center-right figures in its ranks and had the support of liberals hoping it would provide a positive “model” for the Middle East.

Reality has turned out differently. A longer work is required to address the many twists of Erdoğan’s years in office, but Çağaptay gives the general contours. This includes his close alliance then bitter break with the network of U.S.-based Islamic preacher Fethullah Gülen, whose supporters are thought to have been behind last year’s military coup attempt. Çağaptay is rightly harsh on both, describing their clash as a “raw power struggle” far removed from the self-righteous rhetoric of either side.

Throughout Erdoğan’s career, every short-term setback has actually only empowered him in the long run. Casting himself as a victim boosts his appeal among Turkey’s conservatives. As Çağaptay writes: “Erdoğan’s biggest strength as a politician and biggest weakness as a citizen is that despite being in tight control of the country, he feels as if he is still an outsider.” Today he has reached a sweet spot where he can wave away every unfortunate event as the work of dark forces trying to sabotage Turkey’s historic rise. This rallies enough support to keep him in power, but at the expense of an increasingly paranoid and unstable social fabric. The personality cult around Erdoğan today instrumentalizes Islam to serve a deep-seated ambition for prestige and national assertion as heir of the great Ottoman Empire.

Erdoğan has also been far shrewder than his opponents. Çağaptay writes about how today “the gap between various groups in the Turkish opposition can be wider than the gaps between Erdoğan and his opponents.” The president himself has deftly exploited and exacerbated these divisions, “extending an olive branch to one while persecuting the other.” His authoritarianism is the natural result of a worldview that sees only his movement as the true representative of “the people.” In true populist fashion, “detractors can only be representing foreign interests, acting as ‘proxies’ for outside actors,” writes Çağaptay.

The book strikes a pessimistic tone about Turkey’s future. Çağaptay recognizes that the country has passed a dangerous Rubicon whereby Erdoğan and almost all government officials are today left with “no graceful way to exit the scene.” Amid swirling accusations of corruption and a wild spiral of repressions, many are now making zero sum calculations in which it is either public office or jail.

This being the case, Çağaptay’s sensible diagnosis for bringing Turkey back from the brink - recommitting to the EU and expanding rights and liberties for all - looks rather naïve. Çağaptay suggests that Erdoğan's "iron fist" rule has a natural limit considering the “growing number of middle-class Turks who increasingly want a free society.” This classic liberal theory may apply in some circumstances; it is doubtful whether reality will conform in today’s Turkey.

* A version of this review was first published in the Times Literary Supplement. Follow the Turkey Book Talk podcast via iTunes here, Stitcher here, Podbean here, or Facebook here, or Twitter here.